Hello Sour Brewers!

For those of you who, like myself, participate in Facebook, Reddit, or other online forums that discuss craft beer, you will have inevitably seen someone post the question: “What is the best sour beer for a new sour beer drinker to taste?”. When reading these posts, I have seen answers range from “Don’t let them try any, more for us!” to “Some Cantillon ghost whale that costs $1000+ per bottle” to every other option in-between. Despite the myriad of opinions, many folks will recommend that a new sour drinker should taste some version of the Flander’s Red Ale style.

This style is often recommended because many examples are not only delicious, but also have a few other traits that may ease the uninitiated into enjoying sour beers such as:

- These beers are more commonly available. In fact, the largest production volume for any sour beer in the world is for Rodenbach, a classic example of the style.

- Many examples have some balancing sweetness or a less aggressive souring that won’t “scare off” new drinkers.

- These beers tend not to be heavy on Brettanomyces funk. While personally, I love a good funky barnyard sour, these flavors (like those of many fermented foods) are definitely an acquired taste.

In 2011, when I became interested in brewing my own sour beers, I chose to model my very first sour beer recipe (Dr. Lambic’s Sour Red Ale) after the flavors I experienced in a bottle of one of my favorite American versions of the style, Jolly Pumpkin’s La Roja. In regard to an introductory beer style, my red ale became one of the first sour beers that both my mother and my partner enjoyed drinking.

While Flanders Red Ales, like any well brewed style, can certainly be a great introduction to sour beers, there are also a few drawbacks to the style to be aware of. The first of these is related to the types of acids present in any particular blend. While most sour beer styles derive the majority of their souring from lactic acid, which is typically soft and pleasant on the palate, it is common amongst Flanders Red Ales to employ a higher percentage of acetic acid in their profiles. Acetic acid is the chemical which gives vinegar its characteristic flavor and aroma. Unlike lactic acid, when acetic acid reaches higher concentrations, it can be very harsh on the palate. Some people are put off by even low levels of vinegar flavor and therefore some examples would not make a good intro beer for such a person. The second caution I would offer when selecting a Flanders Red Ale is that some examples are pasteurized to preserve the balance between their sweet and sour flavors. Because this process kills off any living microbes, a pasteurized Flanders Red, unlike many other sour beers, will not be resistant to oxidation. Unfortunately, I’ve had several examples from over the years that had sat on bottle shop shelves for far too long.

Regardless of whether Flanders Red Ales make great introductory sour beers, there is no doubt that well brewed examples are delicious and complex beers well worth your attention. It is the goal of this article to not only provide you with a thorough understanding of the range of the style but also to teach you how to design and brew your own delicious sour red ales.

Understanding Classic Flanders Reds and American Interpretations of the Style

The red ales of Belgium are a style with a history spanning back more than 200 years. The first clear historic examples were brewed in 1820 by the Rodenbach brewery although these sour reds fell into a family of beers that were already being produced within the region. It was a common practice throughout both Belgium and much of Europe to store beer that wasn’t drank fresh in barrels. As these beers aged they would inevitably become either sour, funky with Brettanomyces, or both. In some cases these sour beers were served in this state as a specialty product. More often though, such beers would be blended with younger, fresher, beer to create products that had some of the complexity created by age yet were restrained in their acidity. These blended beers had to be drank fairly quickly in local bars and restaurants to prevent their slow progression back towards more extreme flavors due to the microbes living within them. As modern industry and transportation slowly transformed Europe, breweries had to adapt their processes in order to ship their beers further from the brewery while still retaining the balance they sought. Therefore, if modern breweries want to produce a Flanders Red that will retain some sweetness in the bottle, they do so by pasteurizing their blended beers or by adding an unfermentable (artificial) sweetener to the beer.

Classic Flanders Reds are a wine-like beer with a variety of fruit flavors derived from both the malt and yeast fermentation profiles. The beers can have a subtle level of bitterness but they do not typically have any hop flavor or aroma. Their sourness can range from low and in the background to high and prominent in flavor. Typically, the malty flavors in these beers are balanced opposite to their souring. In other words, highly sour examples tend to be less malty while very malty examples tend to have a low level of souring. Classic examples show a low to moderate level of oak barrel character. This contribution from oak will typically provide some red wine-like tannins to the beer as well as mild levels of vanilla flavor and aroma. Some American examples of the style will push this oak contribution a bit further to produce beers with a high degree of oak flavor that borders on bourbon-like. The classic red coloration in these beers is typically the result of the use of caramelized specialty malts. These malts will provide some of the raisin, plum, and dehydrated fruitcake flavors common to the style. Caramel malts also maintain a perception of sweetness even in examples of the beer that are very highly attenuated and have no fermentable sugars remaining. The other major contributor to the fruit flavors found in these beers is an aggressive ester profile produced by classic “British” strains of Saccharomyces yeast as well as certain strains of Brettanomyces. These fruity esters often take on the flavors of black cherries, oranges, and currants. It is the combination of these complex fruit flavors with the oak tannins that provide both structure in the body and dryness in the finish of these beers, characteristics which are analogous to many dry red wines.

Returning for a moment to the malt character classic to these beers, it is typical to taste the bready and crackery contributions of Vienna or Munich malt as well as light chocolate flavors and the melanoidin, caramel, and candy notes of certain specialty caramel/crystal malts. This style does not typically showcase any roasted or smoky characteristics. Most classic examples have a moderate alcohol content, ranging from about 4.5 to 6.5% ABV, although some specialty blends are produced that may have higher ABVs. The mouthfeel and body can be quite variable based on both blending or pasteurization/sweetening and may range from creamy and full bodied to sharp, tannic, and bone dry. Additionally, carbonation can range from low to medium in most traditional examples and may trend higher in bottle conditioned or American versions.

Rodenbach Caractère Rouge, a special edition blended with cranberries, raspberries, and cherries. Photo © Ralph Marana.

Both the total acidity and types of acids present can vary significantly in different examples of the style. In traditional Flanders Reds, the total acidity is generally low to medium, adding balance to the malt and some interesting dimensions to the flavor without being puckering or intensely sour. Once again, some special release blends by Belgian brewers, as well as many American examples, will push the souring to more aggressive levels. Flanders Red Ale is the only classic style of sour beer in which it is common to find examples that utilize a higher proportion of acetic acid than lactic acid in their flavor profiles. However, it is important to realize that most examples that do feature a significant portion of acetic acid in their blending are also examples with a relatively low total acidity. When an equivalent measurement of acetic acid (produced by Acetobacter or Brettanomyces) is compared to either lactic acid (from bacteria such as Lactobacillus or Pediococcus) or malic or citric acids (contributed by fruit additions), the acetic acid will taste sharper and more biting. At levels over a certain threshold, acetic acid will not only taste harsh but it will taste distinctly like malt vinegar. Good examples of the Flanders Red Style may make use of enough acetic acid to give the beer some mild acetic complexity and roundness to the souring profile without being harsh or overtly vinegary. Examples of the style with higher total levels of acidity should therefore feature a higher proportion of lactic acid than acetic acid in order to retain their drinkability. This rule is generally true for sour beer of any style and is the norm in lambic beers. It is not a requirement for these beers to contain acetic acid. Traditional or modern interpretations of the style that feature only lactic acidity should not be considered to be “flawed”.

The wine-like and fruity profile of Flanders Red Ale naturally lends itself to blending with real fruit and there are a number of examples of American and European sour beers made using this approach. The most common fruit to be blended with this style of base beer is cherries, although a variety of other fruits will also produce delicious results. While classic examples of the style do not contain fruit, I do suggest tasting fruited versions as well for palate training and I will discuss best practices for making your own sour reds with fruit.

Overall, a Flanders Red Ale will embody a four-way interplay between fruit-like esters, specialty malt flavors, oak character, and acidity. As with any well made beer, it is not expected that these components will have the same degree of intensity in every example. Excellent examples of the style will strike a balance that provides nuance and complexity while retaining a high degree of drinkability. These beers, like Belgium’s other prominent sour style lambic, are meant to be drank by the pint. All things considered, if you can’t sit down and easily drink a whole pint of one of these beers, then it probably isn’t a very good example of the style.

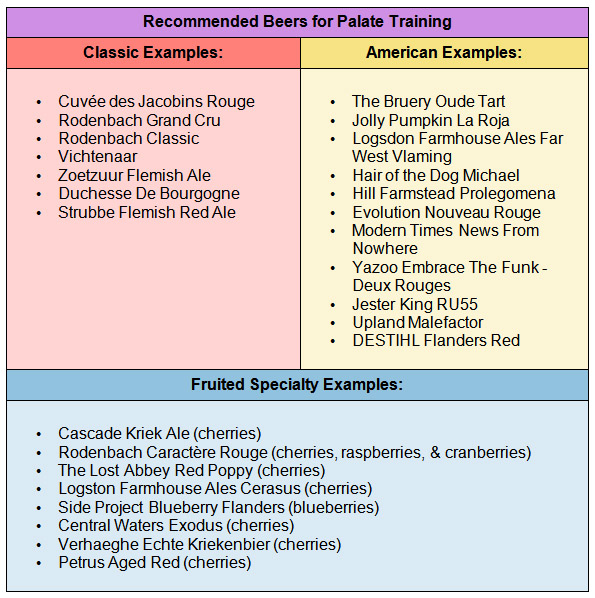

It is the goal of this article to provide you with a thorough understanding of Flanders Red Ales, including the concepts you will need to both evaluate examples of the style and brew your own. I feel that an important first step to any attempt to brew a classic style is to seek out and taste great commercial examples. To that end, I have compiled a table of examples to get you started:

Designing a Sour Red Ale Recipe

When it comes to thinking about beer recipe design and brewing process, it’s important to decide what your goals for the beer are. For example, if you are brewing for competition, it is important to remain within the BJCP style guidelines to a fairly strict degree. If that is your goal, I would recommend producing a version with high levels of both maltiness and fruitiness. Oak character should be medium and acidity should be medium to low. Brettanomyces characteristics should be low and of the fruity to leathery variety. Competition examples should be allowed to develop some noticeable acetic acid but should not taste or smell purely like vinegar. The appropriate blend of acids in Flanders Red has been a point of confusion amongst homebrewers in the past. In my opinion, this may have been due to both a lack of good imported examples and unclear wording in the 2008 BJCP Guidelines. Thankfully, the recently released 2015 BJCP Guidelines make a clear statement to the fact that these beers should not taste or smell aggressively of vinegar.

Competitions aside, if your goal, like mine, is simply to create a delicious example of a Flanders or Sour Red Ale that captures your favorite aspects of the style, then you get to have a great deal more flexibility and creativity!

Malt Choices:

Classic examples of the style make use of either Vienna or Munich as the base malt with an addition of various crystal or caramel malts for both color and flavor contributions. Some traditional examples use corn as an adjunct sugar source to lighten the impact of a malt like Munich, which if used for 100% of the base could produce a heavier maltiness (think Octoberfest lager) than may be desired.

Classic examples of the style make use of either Vienna or Munich as the base malt with an addition of various crystal or caramel malts for both color and flavor contributions. Some traditional examples use corn as an adjunct sugar source to lighten the impact of a malt like Munich, which if used for 100% of the base could produce a heavier maltiness (think Octoberfest lager) than may be desired.

When choosing your malt bill for this style, you should decide how impactful you would like the malt character to be in your finished product. I would think about this in regard to the intensity of character you are trying to achieve in regards to graininess, caramel, and dehydrated fruit flavors. You can adjust the overall graininess with your base malt choice. Using a higher percentage of Vienna, Munich, or both will ramp up this characteristic in your beer. I would advise against using Munich as the sole base malt because it often has a lower diastatic power (fewer active enzymes) which can make it difficult for the mash to fully convert. If you’re going for maximum maltiness, I would recommend a 75% blend of Munich with 25% Vienna for the beer’s base malt. If you are going for a more restrained malt presence I would suggest blending Vienna down with British or American pale malt. If you’re less worried about stylistic points, I feel that Pilsner malt can make a very nice contribution to this style. A base of 50% Pilsner with 50% Marris Otter would provide a pleasant graininess as well as some more aromatic biscuit and cracker notes to the beer. On small scales, I feel that using corn to cut a malt bill is not worth the hassle. If you’re looking to tone down graininess, just use American pale malt or cut a Vienna base with something like 10% dextrose.

The choice of what types and percentages of crystal / caramel malt to use in a sour red ale is an important one. Regardless of the types chosen, I would recommend keeping the total percentage of crystal / caramel malts in the grain bill to under 15%. Anything higher than this, in my experience, is simply too intense and can be cloying. This remains true even in a highly attenuated sour beer. Crystal malts in the 40 to 80 lovibond range will provide a beer with caramel, toffee, and candy-like flavors. Crystal malts in the 120 to 150 lovibond range, as well as Special B (220 L), will provide flavors of bittersweet caramel and dehydrated fruit flavors such as those of raisins, prunes, fruitcake, and currants. Excellent sour red ales can be made using crystal malts from the lower or higher lovibond classes, or both. If choosing to use a higher percentage of crystal malts in the 40 to 80 lovibond range, I would recommend also choosing a mashing and fermentation profile to drive attenuation. These caramel candy flavors can add a wonderful dimension of complexity and balance to highly attenuated (dry) sour beers. However, in less attenuated or back-sweetened versions of the style, these flavors can come across as cloying and amateurish. The dehydrated fruit flavors gained from use of higher lovibond crystal malts in more restrained proportions will work well in dry or sweet versions of the style, but are in my opinion your only choice when producing sweetened or pasteurized Flanders Red Ales.

There are a number of specialty wheat and rye malts now available on the market that can also add complexity to a sour red ale. These are not a traditional component of Flanders Reds, but caramel wheat or caramel rye can be used as a replacement for 40 to 80 lovibond crystal malts and will add a unique dimension to your beer’s malt profile. On the same train of thought, I have also incorporated plain white wheat malt into some of my sour red ales as a way to add complexity to the body and mouthfeel of the finished beer.

Hops:

Sour red ales generally do not benefit from having significant hop character. Traditional or modernized versions of the style can be produced without the use of any hops in the recipe. If you do decide to add hops to the beer (a legal requirement for commercial brewers in many situations), you should keep the total IBUs under 10 in most cases to prevent the inhibition of Lactobacillus bacteria during fermentation. Hops should be added early in the boil or during mashing to produce a light bittering without contributing significant hop flavor or aroma to the beer. When choosing the hops to use, you should avoid hops with highly aromatic oils such as American, Australian, or New Zealand citrus, pine, melon, or tropical fruit varieties. Hops such as Magnum, Goldings, or Sterling would all be good choices.

Sour red ales generally do not benefit from having significant hop character. Traditional or modernized versions of the style can be produced without the use of any hops in the recipe. If you do decide to add hops to the beer (a legal requirement for commercial brewers in many situations), you should keep the total IBUs under 10 in most cases to prevent the inhibition of Lactobacillus bacteria during fermentation. Hops should be added early in the boil or during mashing to produce a light bittering without contributing significant hop flavor or aroma to the beer. When choosing the hops to use, you should avoid hops with highly aromatic oils such as American, Australian, or New Zealand citrus, pine, melon, or tropical fruit varieties. Hops such as Magnum, Goldings, or Sterling would all be good choices.

While there are practically no commercial examples on the market, I could see a dry-hopped sour red ale making for an interesting beer. If you do decide to experiment with dry-hopping, keep in mind that this would no longer be a true Flanders Red and would be unlikely to fair well in competitions as such. If dry hopping such a beer I would choose classic noble hops or varieties that produce tropical fruit aromas without high levels of pine character. The former varieties may play very well with various Brettanomyces characteristics while it has been my experience that hops that produce aromas of pine, garlic, or onion do not.

Water:

I always take a fairly simplistic approach towards my brewing water. I brew using reverse osmosis or distilled water and then add back enough calcium to ensure a healthy fermentation and yeast flocculation. These recommendations come from Gordon Strong in his book Brewing Better Beer. When brewing sour red ales using this approach, I would recommend adding 1/2 teaspoonful each of calcium sulfate and calcium chloride (per 5 gallons) to the mash if you desire a generally smooth character that doesn’t promote malt flavors over other characteristics in the beer. If you would like to produce a maltier sour red, then I would add 1 full teaspoonful of calcium chloride per 5 gallons of water to the mash, forgoing any use of calcium sulfate (gypsum). I also always use one dose of the yeast nutrient Servomyces per 5 to 10 gallon batch to replace micronutrients that may be lost from the reverse osmosis filtering process.

Yeast, Bacteria, and Fermentation:

Yeast, Bacteria, and Fermentation:

The choices made in strain selection, pitch rates, and fermentation profile are arguably the most important decisions affecting a beer’s overall character and quality. I feel that this is especially true for sour beers, many of which obtain their most dominant characteristics during fermentation and aging. There a number of options available when it comes to fermenting sour red ales and many of these options can be tweaked to adjust the flavor profile of your finished beer.

There are several combination blends of yeast and bacteria produced by various yeast labs to ferment traditional Flanders Red Ales. These Include:

- Wyeast Roeselare Blend (3763) – This may be the oldest blended sour culture on the market and has been shown over the years to be able to produce very good sour red ales. During its first generation it tends not to produce a great deal of sourness so it a good choice for less sour, more malty red ales. If you want to bump up the sourness of this blend, consider pitching a standalone Lactobacillus culture either with the blend or up to several days before pitching the blend.

- White Labs Belgian Sour Mix (WLP655) – If pitched fresh, this culture tends to produce a beer with moderate sourness within about 3 months time.

- White Labs Flemish Ale Blend (WLP665) – I have not personally used this strain but based on my experience with their Belgian Sour Mix, I expect this to produce good results as well. According to the Milk The Funk group, this blend produces a darker, more complex array of stone-fruit flavors than WLP655.

- East Coast Yeast Flemish Ale (ECY02) – This blend is based on a Belgian strain of Saccharomyces as well as several strains of Brettanomyces, Lactobacillus, and Pediococcus chosen to produce moderate to high acidity and complimentary stone fruit and funky leather flavors.

- Gigayeast Sweet Flemish Brett (GB144) – This Saccharomyces & Brettanomyces blend is designed for low attenuation and low acid production. This blend would be a good choice for sweeter, more malt forward versions of the style.

- Blackman Yeast Flemish Sour Mix (F4) – This is a dry yeast blend containing both Lactobacillus and Pediococcus intended to produce medium souring as well as a blend of fruit and spice. I have not personally used this product or any of the Blackman dry yeast blends, but I can see this as being a great product for both simplicity of use and for its ability to give brewers from countries without access to fresh liquid yeast/bacteria cultures a reproducible mixed fermentation option.

When pitching a mixed culture to ferment your sour red ale, the ratio of various bacteria and yeast strains has already been determined by the lab producing the blend. This ratio will largely determine the balance of components like lactic acid, acetic acid, esters, and phenols in the finished beer. This is not to suggest that you still cannot control the intensity of those flavors.

Fermentation temperature is one of the most important factors relating to fermentation health and the intensity of various products of fermentation. In general, the first 48 to 96 hours of fermentation for any beer are the most important when it comes to temperature stability. This means using some type of setup that actually measures the temperature of your beer and cools or heats it as needed to maintain a set point. The biggest difference between professionally brewed beer and most home brewed beer is fermentation temperature control. If using any of the above blends, a stable temperature set somewhere between 65 to 72 degrees throughout primary fermentation is appropriate. Additionally, I would recommend keeping an eye on your fermentation activity and increasing the temperature a few degrees during the last 10 to 20% of standard ale attenuation. This generally correlates to when you begin to see a significant slowdown in airlock activity. These measures drive a healthy and active fermentation by Saccharomyces that helps to avoid off-flavors such as acetaldehyde or fusel alcohol.

Fermentation temperature is one of the most important factors relating to fermentation health and the intensity of various products of fermentation. In general, the first 48 to 96 hours of fermentation for any beer are the most important when it comes to temperature stability. This means using some type of setup that actually measures the temperature of your beer and cools or heats it as needed to maintain a set point. The biggest difference between professionally brewed beer and most home brewed beer is fermentation temperature control. If using any of the above blends, a stable temperature set somewhere between 65 to 72 degrees throughout primary fermentation is appropriate. Additionally, I would recommend keeping an eye on your fermentation activity and increasing the temperature a few degrees during the last 10 to 20% of standard ale attenuation. This generally correlates to when you begin to see a significant slowdown in airlock activity. These measures drive a healthy and active fermentation by Saccharomyces that helps to avoid off-flavors such as acetaldehyde or fusel alcohol.

It is safe to assume that in any mixed culture, the Saccharomyces strains will be the most aggressive fermentors, typically outcompeting Brettanomyces, Lactobacillus, and Pediococcus during the first 3 to 10 days of fermentation. The temperature at which you decide to ferment during this period of time can be adjusted up or down depending upon the desired intensity of the byproducts you are looking for from Saccharomyces. In general, higher temperatures (70-75 F) will result in more ester and phenol production. Therefore if you are using a blend with an English type strain, higher early temperatures will drive the production of more fruity esters. Depending on the Brettanomyces strains present, some of these esters may be modified to give more leathery and earthy notes. If your blend contains a phenolic Belgian Saccharomyces strain, higher temperatures will also drive the production of more spicy, clove-like phenols. Once again, depending on which Brettanomyces strains are present, some of these phenols can be converted during the aging process to more funky, barnyard, hay, cheese, and animal notes. I would recommend using caution when combining certain highly phenolic Belgian Saccharomyces strains with a Brettanomyces strain for the first time. Some strains of Brettanomyces can produce smoky aromas and flavors from phenolic compounds. I personally find these to be unpleasant in any sour beer and they are definitely not meant to be a component of traditional Flanders Red Ales.

When you choose to ferment with a mixed culture for the first time, I would recommend pitching it using the same rates suggested by Jamil Zainasheff’s “Mr. Malty” Yeast Calculator. When using this yeast calculator choose the options for a standard ale and for no stir plate. This means using multiple packages or making a starter in many situations. These starters can be made using most of the standard practices used to grow yeast cell counts for non-sour fermentations. I would recommend against using a stir plate to grow up any mixed culture that contains bacteria (Lactobacillus or Pediococcus in these examples). The continuous oxygenation provided by a stir plate benefits Saccharomyces and Brettanomyces yeasts but will not provide any growth boost for bacterial cells in the culture. This could lead to a propagated culture with a higher yeast to bacteria ratio than initially intended by the lab.

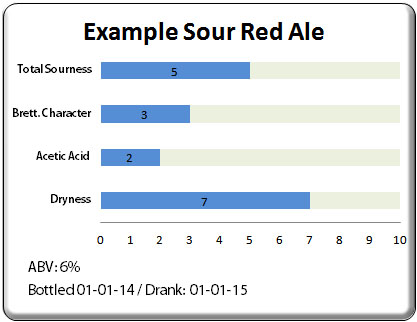

When it comes to acidity, most of the mixed cultures available commercially that contain lactic acid bacteria will produce a beer with a low to medium level of sourness (ranking 2 to 6 on the scale used on this site). If the aging beer has little to no exposure to oxygen, this acidity will be almost entirely composed of lactic acid and will be fairly soft on the palate. As oxygen exposure increases, these beers will become somewhat more sour (ranking 4 to 8) and this acidity will be produced by a blend of both lactic and acetic acid. At these levels, this souring, while sharper, is typically still pleasant. If too much oxygen exposure occurs for too long of a time, the acetic acid level in the beer will become too high and the beer will be bracingly sour but also harsh and biting.

If you desire a higher level of lactic souring, I have found that the best way to achieve this is to pitch a pure Lactobacillus culture up to several days before pitching the mixed culture that contains your yeast. In the case of my sour red fermentations, this first stage of Lactobacillus fermentation doesn’t necessarily produce a high level of acidity early on, but I believe provides a much higher Lactobacillus cell count which does sour the beer significantly over the first 3 months of aging. Therefore, it may be possible to achieve the same result by simply pitching greater cell counts of Lactobacillus at the same time as the initial mixed culture pitch.

While it is not my preference for the style, there are some examples of the style that have a high degree of maltiness with a low level of acidity that is entirely composed of acetic acid. As long as the total souring is low (zero to 3 on the scale used on this site), then 100% acetic acid sourness is generally not offensive or harsh. However, these beers may have a more distinct vinegar aroma than beers utilizing a low intensity blend of both acetic and lactic acid. Regardless, if you would like to produce a beer with a low level of acetic-only souring, then I would recommend avoiding mixed cultures that contain lactic acid bacteria and rather use one that only contains Saccharomyces and Brettanomyces. When supplied with low levels of oxygen, such as the micro-oxidation that occurs during oak barrel aging or when aging in a partially full carboy, the Brettanomyces in these cultures can (strain dependently) produce acetic acid at these relatively low levels.

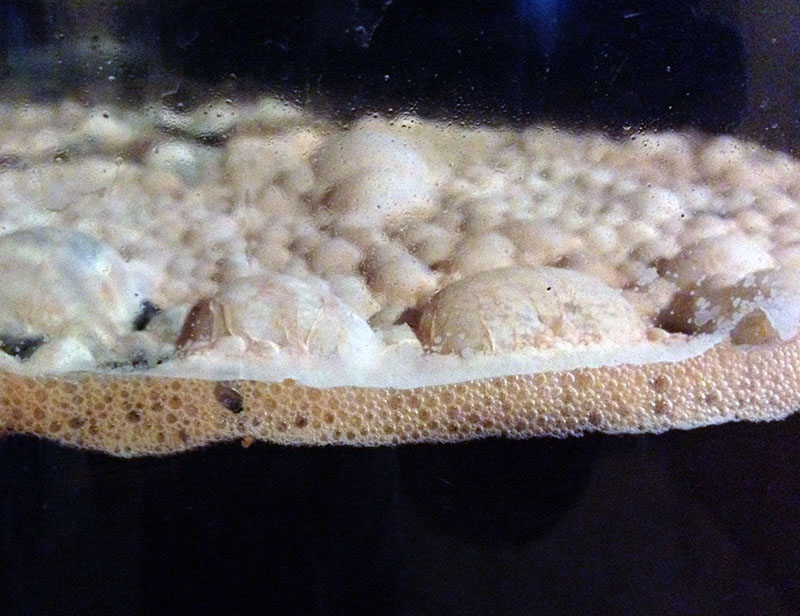

The Acetobacter family of acetic acid producing bacteria are well known beer spoilage organisms that are traditionally used in the fermentation of vinegar. While these bacteria may play some role in the development of acetic acid for traditional Belgian breweries that produce Flanders Reds, I feel that they should never be intentionally added to a batch of beer. In small volumes of beer or single barrels, these bacteria can turn the entire batch into harshly acetic malt vinegar. Most sour brewing programs will dump and destroy these barrels. Acetobacter is spread by fruit flies so whether fermenting in carboys or barrels, make sure to clean up any spilled or leaking beer quickly and if needed set traps to keep fruit flies out of your beer aging spaces.

When aging a Flanders Red Ale for 6 to 12 months in glass, stainless, or PET plastic (Better Bottles), you may find that your malt character, ester profile, and lactic acidity are all tasting great, but the beer never developed any acetic character. In these cases, if you want to bump up the acetic acid levels I would strongly advise against purposefully trying to oxidize the beer. While this may have the desired effect on the acetic acidy of the beer, it could also negatively impact the malt flavors through staling. Rather, in these situations, I would recommend simply purchasing a quality malt vinegar and adding in a small amount to taste. If this seems like cheating to you, then purchase a vinegar mother culture and ferment the vinegar yourself before adding it.

For brewers who would like to explore more advanced multi-step fermentations, you can create your own blends of Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces, Brettanomyces and Pediococcus. These organisms can be pitched together or pitched at different times to attempt to produce different flavor profiles. I have discussed these types of fermentations in my articles on Dr. Lambic’s Sour Red Ale and Understanding, Brewing, and Blending a Lambic Style Kriek. These multi-step fermentations are designed to help the bacteria Lactobacillus compete with Saccharomyces for access to fermentable sugars, allowing them to grow higher cell counts and produce more lactic acidity. In my opinion, these processes are one of the most reliable ways to produce sour beer of any type with higher levels of clean lactic acidity.

Oak Character and Aging:

When it comes to aging sour red ales, a brewer typically has several choices:

Oak Barrels – Impart both oak character and micro-oxygenation.

Oak Barrels – Impart both oak character and micro-oxygenation.- Oak Foudres – Depending upon size, these often impart less distinct “oak” flavor. Due to their very low surface area to volume ratio, foudres tend to provide a very slow and controllable micro-oxygenation.

- Glass Carboys & PET Plastic (Better Bottles) – These options can allow a brewer to virtually eliminate micro-oxygenation if the beer level is kept very high (to the neck) and samples are taken rarely or the headspace is thoroughly flushed with CO2 after sampling. Airlock choice and maintenance (keeping them filled with fluid) also plays a large role in oxygen pickup. If higher levels of micro-oxygenation are desired to boost acetic character, keep the beer level lower and sample more frequently, monitoring the beer for acetic development.

- Stainless Vessels – Professional conicals or other stainless aging tanks offer the potential to completely eliminate acetic character in any sour beer if desired. However, long aging times typically make the use of these tanks too costly to be feasible.

Food Grade Plastic Totes – There are several large volume food grade plastic vessels available in the brewing, cider making, and food processing industries. These vessels can make attractive options for the aging of sour beers due to their lower costs and often barrel-like oxygen permeability.

Food Grade Plastic Totes – There are several large volume food grade plastic vessels available in the brewing, cider making, and food processing industries. These vessels can make attractive options for the aging of sour beers due to their lower costs and often barrel-like oxygen permeability.

Your choice of aging vessel is an important one to consider dependent upon the mixed culture and fermentation processes that you choose. Micro-oxygenation is a complex topic when it comes to any mixed culture containing Brettanomyces. Depending upon the strains involved, oxygen exposure during aging may have positive or negative effects. Oxygen exposure will cause most strains of Brettanomyces to produce some level of acetic acid during the aging process. This of course may be a good or bad thing depending upon your desired flavor profile for the beer. Additionally, because oxygen helps Brettanomyces multiply cells, micro-oxygenation may help Brettanomyces develop an array of positive aroma and flavor compounds. Much of the way Brettanomyces will react to aging conditions is related to the individual strains being used. This situation typically creates the need for a brewer to experiment with their brewing and aging processes to see how the strains they are using react. If you find that you’re getting results that are undesirable, consider altering your processes or aging systems to avoid those flavors. An example of the complexity of this topic can be seen amongst professional sour beer brewers in regards to their barrel top-off practices. About half of brewers choose to top off their barrels at some point during the aging process and the other half do not. Interestingly, there does not seem to be any strong correlation between whether a brewer tops off or not to the acetic acid levels in their finished sour beer. It is my opinion that this is largely due to strain to strain variation as well as the specific methods and conditions being employed during the aging process. All things considered, no microorganism (including Acetobacter, Brettanomyces, Saccharomyces, Lactobacillus, or Pediococcus) can produce acetic acid in the absence of oxygen, it’s simply a metabolic impossibility.

I would recommend the following for any brewer developing a start-up sour program or for homebrewers trying out these techniques for the first time:

- Age your first attempt sour beers with the goal of avoiding oxygen pickup wherever possible.

- If you have done everything possible to avoid oxygen and your beer is harsh or acetic after aging, re-evaluate all of your transfer and aging processes, if there is nothing that could be improved, then consider selecting a new mixed culture to work with.

- If after a long aging period, the beer is lacking in significant Brettanomyces character development, consider processes that will allow for some additional micro-oxygenation.

- If allowing for more micro-oxygenation results in a strong development of acetic character before the development of desired Brettanomyces flavor and aroma, consider selecting a new mixed culture.

- Keep detailed records of your processes and aging conditions to aid in repeatability and strain selection.

- In any mixed culture fermentation, expect some degree of vessel to vessel variability and plan accordingly as to how to deal with that variability with methods such as blending or producing small batch releases.

-

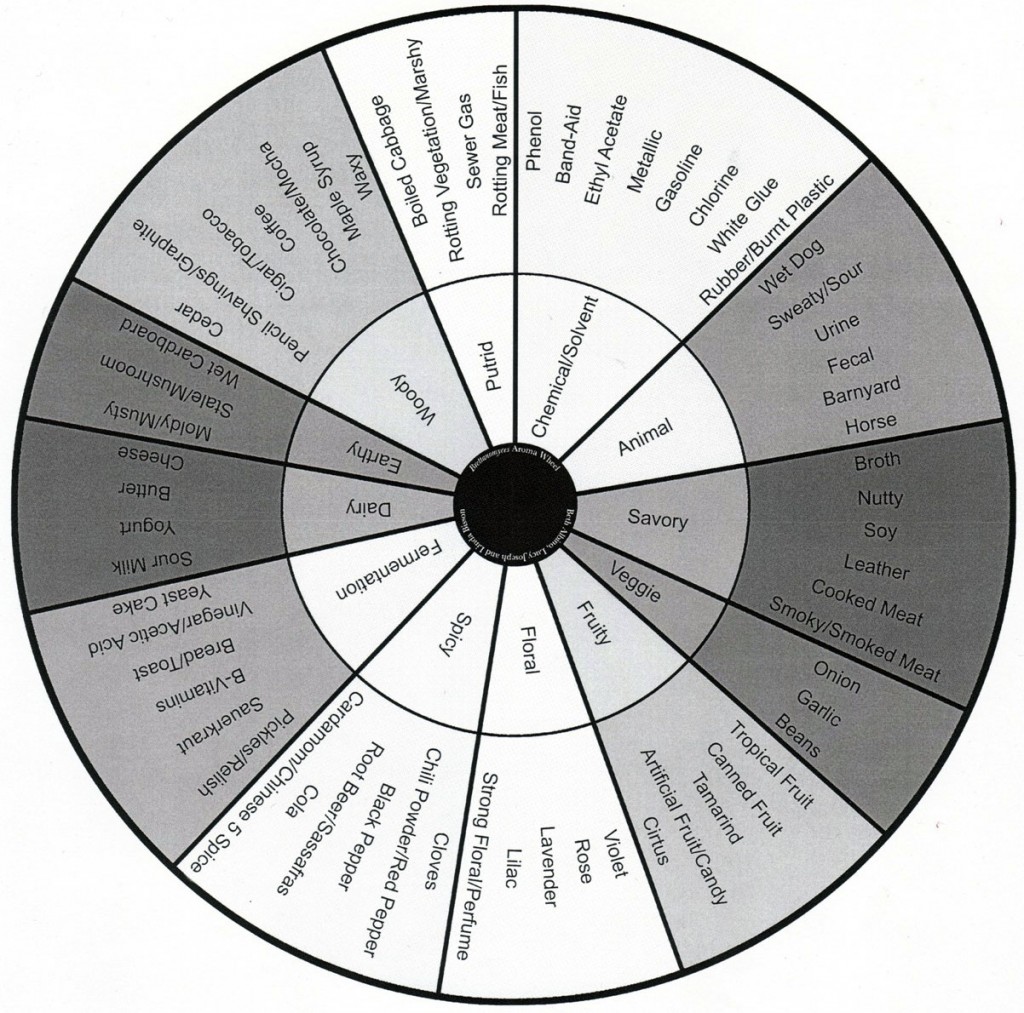

Not every variety of Brett “Funk” is something you want in your beer. This Brettanomyces flavor and aroma wheel helps to group and categorize the various potential byproducts of Brettanomyces aging.

Don’t be afraid to dump bad sour beer. Trying to blend out almost any off-flavor is a waste of time and good beer. These flavors include but are not limited to: DMS, Diacetyl, Acetaldehyde, Unwanted Brettanomyces Characteristics (Chemical, Solvent, Putrid, Wet Dog, Smoky, Medicinal, etc), Fecal, Vomit, Stinky Feet, Cheesy, Stale/Papery, etc.

While traditional examples of Flanders Red Ale typically have a low to medium level of oak character that is restrained to the tannin and light vanillin contributions of oak, sour red ales in general can work well with a wide variety of wood and oak flavors. If aging in barrels, your choice of barrel will largely dictate what characteristics you achieve. If you are looking to create a more traditional example, then choose barrels that have been largely stripped of their character. Barrels that have been used to age several generations of beer make good choices as would barrels used to age dry white wines. For options that may enhance the fruit characteristics of your sour red ale, I would look towards barrels that have housed red wines or fruit brandies. For the signature characteristics of bourbon or other distilled spirits, barrels that have housed these products can add a non-traditional yet delicious new element to a sour red ale.

For homebrewers using new oak chips, cubes, spirals, or honeycombs, you can use the same basic logic for your oak selections. If producing a traditional example, consider using oak that has already been aged in at least one batch of beer. Alternatively, some of the distinct “new” flavors of toasted oak can be extracted by one or more rounds of boiling the oak in water before use. If not using one of these methods to tone down the oak, I would not use chips for a traditional example of the style. Using about one ounce of fresh light or medium toast oak cubes in a five gallon batch for around 3 to 6 months will give you a fairly restrained and balanced contribution. If you are looking to add more bourbon-like oak flavors to your beer, go with fresh medium to high toast and consider using 2 or more ounces per 5 gallons. Soaking oak chips in wine or spirits doesn’t really contribute the characteristic flavors that you’re looking for in the finished beer. Rather, homebrewers have the flexibility to choose their favorite wine or spirit and blend some directly into the finished product to taste.

For homebrewers using new oak chips, cubes, spirals, or honeycombs, you can use the same basic logic for your oak selections. If producing a traditional example, consider using oak that has already been aged in at least one batch of beer. Alternatively, some of the distinct “new” flavors of toasted oak can be extracted by one or more rounds of boiling the oak in water before use. If not using one of these methods to tone down the oak, I would not use chips for a traditional example of the style. Using about one ounce of fresh light or medium toast oak cubes in a five gallon batch for around 3 to 6 months will give you a fairly restrained and balanced contribution. If you are looking to add more bourbon-like oak flavors to your beer, go with fresh medium to high toast and consider using 2 or more ounces per 5 gallons. Soaking oak chips in wine or spirits doesn’t really contribute the characteristic flavors that you’re looking for in the finished beer. Rather, homebrewers have the flexibility to choose their favorite wine or spirit and blend some directly into the finished product to taste.

Fruit Additions:

Sour red ales make a versatile base for the addition of various fruits and there are many commercial examples that exemplify this. Cherries are by far the most common fruit added to these beers but a wide variety of other fruits also make great choices. Because sour red ales generally have more intense flavors than, for example, golden sours, fruits with intense flavors will make better choices for a signature flavor addition while more subtle fruits may be added for background complexity and aroma. While this is certainly not an all-inclusive list, I would consider cherries, raspberries, blueberries, cranberries, and grapes to be prime candidates for signature flavor additions. When adding fruit, go with a rate of around one pound per gallon for an intensity that matches the malt and yeast characteristics found in many sour red ales. If you would like the fruit flavors to stand out distinctively above the other flavors in the beer, go for a rate of around 2 pounds per gallon. At rates of 3 or more pounds per gallon, your beer will begin to take on a more wine-like character found in certain fruit lambics such as Drie Fonteinen’s Intense Red Oude Kriek.

A blend of frozen berries would make a nice addition to a sour red ale, especially at times of the year when fresh fruit is unavailable.

Fruit can be sourced fresh, frozen, pureed, or dehydrated. If using dehydrated fruit consider rinsing it briefly in a colander with near boiling water to strip away surface oils that are typically added to dehydrated fruits. For fresh fruit, always thoroughly rinse the fruit to remove any surface dirt or pesticides. I always recommend waiting until a beer tastes like it could be served as is before adding fruit. Fruit should not be used as a way to try to fix a flawed beer. Once your beer is tasting good and with the aging characteristics that you prefer, add the fruit. You will notice a second round of fermentation occur as Brettanomyces becomes active and consumes the fruit sugars. After this active fermentation is complete and the beer settles (usually around 1 month), I would recommend tasting the beer once a month therafter. In most cases the fruit flavors will peak at about 3 months and the beer will be ready for serving or packaging.

Targeting a Sweet to Sour Balance:

Sour red ales are one of the few styles of sour beer which may be served or packaged with some level of residual sweetness in the finished product. I personally prefer my sour beers to be highly attenuated, but I have drank a number of pleasant examples of this style which were not. Here are some things to consider in regards to this:

- Mixed culture fermentations will, by their nature, eventually become highly attenuated. If you prefer the style dry, then mash at a lower temperature for higher attenuation and age the beer until you are happy with it. Stable, well attenuated sour beers are capable of being served by draft or safely bottled.

- If you intend to serve the beer on draft only, then you have several options for creating a beer with more balance between sour and sweet. You can:

- Mash higher and utilize a recipe and process which will retain some residual sweetness while developing acidity rather quickly. Techniques like multi-step fermentation can produce a nicely sour red ale in around 3 to 6 months that still retains a fuller body and more malt sweetness.

- Blend an aged beer that is both sour and highly attenuated with a sweeter younger version of the same recipe.

- Blend in a fruit addition and chill the beer down for serving before Brettanomyces has a chance to referment the fruit sugars. Chilling the beer will significantly slow Brettanomyces but not stop it so this is still only an option for draft beer.

- If you intend to bottle a sour beer with residual sweetness you have only two options:

- Ferment and/or blend the beer to the point where you want the flavors to remain and then pasteurize the beer, thus killing all of the microbes which could referment it.

- Use an unfermentable artificial sweetener on a well attenuated and stable sour beer. (Note: I really don’t recommend this option. It just doesn’t fit well within my craft beer world view.)

Ending Thoughts

Flanders Reds and the closely related family of sour red ales being brewed in the American craft beer scene can be some of the most versatile and delicious sour beers on the market. Their flavor balance and quality often make them an excellent choice for new sour beer drinkers and their relatively straightforward brewing methods make them an excellent choice for brewers looking to take the plunge into the sour brewing abyss. I hope that this article has given you an understanding and respect for the style, as well as inspired you to give one of these excellent beers a try in your own brewery. As always, please feel free to e-mail me with any questions.

Cheers and Happy Brewing!

Matt “Dr. Lambic” Miller

References:

“BJCP Style Guidelines.” BJCP Style Guidelines. Beer Judge Certification Program, n.d. Web. 18 May 2015.

Goodwin, Jay, and Scott Moskowitz. “The Sour Hour” The Sour Hour. The Brewing Network. Concord, CA. Radio.

“Mixed Cultures.” Milk The Funk Wiki. Eric Bandauski, Et Al., n.d. Web. 18 May 2015.

Tonsmeire, Michael. American Sour Beers: Innovative Techniques for Mixed Fermentations. Boulder, CO, USA: Brewers Publications, 2014. Print.

Zainasheff, Jamil, and John J. Palmer. Brewing Classic Styles: 80 Winning Recipes Anyone Can Brew. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications, 2007. Print.

Zainasheff, Jamil, and John Plise. “The Jamil Show / Flanders Red Ale” The Jamil Show. The Brewing Network. Concord, CA. Radio.