Fast Souring with Lactobacillus – Best Practices, Sensory, & Science

Hello Sour Brewers!

There are a number of brewing situations and recipe designs where both craft and home brewers would like to establish a nice clean baseline level of lactic acidity in their beers within a short period of time. In order to accomplish this, brewers turn to the Lactobacillus family of lactic acid producing bacteria because these bacteria are both easy to work with and readily available both as pure cultures and naturally on many base malts. In order to accomplish this goal, several methods have been developed to allow Lactobacillus to multiply and ferment lactic acid in the wort before it undergoes a standard fermentation by Saccharomyces (brewer’s yeast) or Brettanomyces. There are several process based issues that arise when attempting to give Lactobacillus sole reign over your wort, and for many brewers the results of such attempts have been lackluster or tainted by off-flavors. Despite this, many brewers have successfully used these methods to produce well-made sour beers with clean levels of lactic acidity.

The goal of the first part of this article is to review the various methods used to produce fast souring in beer and to discuss the best practices to follow when employing these methods. The second component of this article will be a discussion of how to analytically taste your beers in order to detect the various common off-flavors that can arise from fast-souring processes. Finally, a third element of this discussion with center on the science behind these fermentations, with a focus on the various unwanted bacteria that can compete with Lactobacillus. We will review why these bacteria produce the off-flavors that they do and why the best-practices reviewed in part one help to ensure that these bacteria are kept at bay.

Part 1 – Fast Souring Methods & Best Practices

The Sour Mash

Sour mashing is a process in which a typical mash is conducted, but is then allowed to remain warm for up to several days after an inoculation with Lactobacillus. This inoculation can come from either a pure culture of Lactobacillus, a Lactobacillus starter, or from the addition of a small portion of un-mashed base grain, which will naturally have one or more wild stains of Lactobacillus on its husks. After a certain level of souring has been achieved, the mash is sparged as normal and followed by standard boiling and cool-side fermentation practices. The benefit of this method is that Lactobacillus and any other bacteria present in the mash will be killed by the boil and only sanitized beer will move forward into fermentation equipment. The downside of this process is that, of the three methods we will discuss, this one is the most difficult to control and the one most likely to yield off-flavors. The following practices will help you gain the best results from a sour mash, but as we will discuss in Part 3, are not a guarantee of success.

Sour mashing is a process in which a typical mash is conducted, but is then allowed to remain warm for up to several days after an inoculation with Lactobacillus. This inoculation can come from either a pure culture of Lactobacillus, a Lactobacillus starter, or from the addition of a small portion of un-mashed base grain, which will naturally have one or more wild stains of Lactobacillus on its husks. After a certain level of souring has been achieved, the mash is sparged as normal and followed by standard boiling and cool-side fermentation practices. The benefit of this method is that Lactobacillus and any other bacteria present in the mash will be killed by the boil and only sanitized beer will move forward into fermentation equipment. The downside of this process is that, of the three methods we will discuss, this one is the most difficult to control and the one most likely to yield off-flavors. The following practices will help you gain the best results from a sour mash, but as we will discuss in Part 3, are not a guarantee of success.

Best Practices when Sour Mashing

- Conduct either a multistep or single infusion mash as dictated by your equipment or recipe.

- After your saccharification rest is complete, reduce the pH of the wort to 4.5 by addition of food grade lactic or phosphoric acid. This can also be achieved by the addition of acidulated malt (added after sacc rest). Acidulated malt drops the pH on average 0.06 to 0.1 per % of the total grist. This equates to about 7-10% of the total grist for any mash that has a pH of 5.2

- Verify your pH using a meter or test strips and adjust as needed before continuing on.

- Make sure to include a mash-out step which raises the temperature above 168° F for at least 10 minutes to ensure enzyme inactivation and a locking-in of your fermentable to non-fermentable sugar ratio.

- Cool the mash to below 120° F, then add Lactobacillus via a pure culture or by adding a small portion of un-mashed base grain. In any of these processes, using a pure culture is likely to yield more predictable results and reduce your risk of contamination by off-flavor producing bacteria.

- Remove oxygen from the mash tun by flushing the vessel with a layer of carbon dioxide or nitrogen. The mash tun should be sealed as best as possible to keep oxygen out during the sour mash. These inert gases can be bubbled through the mash itself or added via a port above the liquid layer as they are both heavier than oxygen and will displace it. If your equipment allows, a slow trickle of inert gas can be used to continually ensure an anaerobic environment during sour mashing.

- If possible, the temperature of the sour mash should be maintained between 112° to 120° F throughout the sour mashing process.

- Check the progress of your Lactobacillus fermentation via a pH meter every 12 to 24 hours. a pH around 3.6 generally equates with a tartness appropriate for styles like Berliner Weisse or Gose. A pH around 3.3 will be strongly sour, on par with many young lambic style beers. Keep in mind that at a pH below 3.4 to 3.5, some strains of Saccharomyces will have difficulty producing a healthy fermentation. In these cases it may be best to use a mixed or 100% Brettanomyces fermentation, as this family of yeast can remain healthy at pH levels down to and possibly below 3.0

- After your wort reaches the desired pH, raise the mash to 170° to 180° and sparge as usual.

- While a starting pH of 4.5 will generally eliminate the risk of bacteria that can cause food poisoning, use caution when tasting the results of a sour mash. Only a low pH and the presence of alcohol from yeast fermentation can ensure that your fermented product is safe to drink.

Sour Kettling

Very similar to the sour mashing process, sour kettling allows you to produce a sour wort that can then be boiled for sanitation before moving it into your fermentation equipment. Overall though, souring in the boil kettle allows for greater versatility and as a process can often be more easily regulated. This method also allows you to choose whether to kill the Lactobacillus before fermentation by yeast or to allow its continued activity in your aging beer. Sour kettling begins with the use of a completely standard mashing and sparging procedure. If you want to kill Lactobacillus before the rest of your fermentation, then you will perform the steps of sour kettling before the boil. Oppositely, if you want Lactobacillus to survive into your final product, then the boil is conducted before the sour kettling procedure.

Very similar to the sour mashing process, sour kettling allows you to produce a sour wort that can then be boiled for sanitation before moving it into your fermentation equipment. Overall though, souring in the boil kettle allows for greater versatility and as a process can often be more easily regulated. This method also allows you to choose whether to kill the Lactobacillus before fermentation by yeast or to allow its continued activity in your aging beer. Sour kettling begins with the use of a completely standard mashing and sparging procedure. If you want to kill Lactobacillus before the rest of your fermentation, then you will perform the steps of sour kettling before the boil. Oppositely, if you want Lactobacillus to survive into your final product, then the boil is conducted before the sour kettling procedure.

Best Practices when Souring in the Kettle

- If choosing to boil at the end, the first step will be to adjust the pH of your wort to 4.5 using either food grade lactic or phosphoric acid.

- If choosing to boil before souring, make sure that your recipe either does not include hop additions or that those additions produce less than 10 IBUs in the finished beer. Too much alpha acid, or hop oils in general, will inhibit Lactobacillus and prevent souring via its fermentation. After boiling, adjust the pH to 4.5 as previously discussed.

- Cool the wort to below 120° F before pitching your culture of Lactobacillus or adding a sack of base malt to the kettle. As in sour mashing, pure cultures are more predictable and less likely to yield contamination by off-flavor producing bacteria.

- Flush the kettle with CO2 or Nitrogen gas and seal it up as best as possible. Consider scrubbing oxygen from the wort by bubbling inert gas through the wort for several minutes. As before, if your equipment allows, these gases can be slowly trickled into the sealed kettle throughout the sour fermentation to maintain an anaerobic environment.

- Maintain the wort at a temperature between 112° and 120° F, if possible.

- Just like sour mashing, check the pH of your wort every 12 to 24 hours.

- When the desired pH has been reached, either conduct a normal boil procedure, or if you have already boiled and wish to maintain Lactobacillus in your final beer, transfer to fermentation vessels using sanitary practices.

Sour Worting in a Fermentation Vessel

This third process assumes that you wish for Lactobacillus to survive and remain active in your fermenting and finished beer. On both a homebrew and commercial scale, it is best to use either pure laboratory-sourced cultures or cultures collected and maintained from starters which have proven to be free of off-flavors and aromas. Doing so, in combination with the other best practices discussed, will virtually ensure that your beer remains free of unwanted microorganisms and their off-flavors. For commercial brewers who cannot heat their fermenters , this process is identical to sour-kettling after a standard boil. When developing recipes for sour-wort beers, the alpha-acid level from hop additions must be restrained to less than 10 IBUs to prevent the inhibition of Lactobacillus.

This third process assumes that you wish for Lactobacillus to survive and remain active in your fermenting and finished beer. On both a homebrew and commercial scale, it is best to use either pure laboratory-sourced cultures or cultures collected and maintained from starters which have proven to be free of off-flavors and aromas. Doing so, in combination with the other best practices discussed, will virtually ensure that your beer remains free of unwanted microorganisms and their off-flavors. For commercial brewers who cannot heat their fermenters , this process is identical to sour-kettling after a standard boil. When developing recipes for sour-wort beers, the alpha-acid level from hop additions must be restrained to less than 10 IBUs to prevent the inhibition of Lactobacillus.

Best Practices When Souring in a Fermentation Vessel

- Mash and Boil your wort as normal. During the boil, adjust the pH to 4.5 using food grade lactic or phosphoric acid.

- Cool the wort to below 120° F and transfer into a sanitized fermentation vessel. Ensure proper closed & sanitary transfer practices. I have run 110° F wort into glass carboys without incident, but I do not recommend that this be done routinely. It is far better to use a stainless vessel (for homebrewers, either 5 gallon Cornelius or half-barrel Sankey kegs work well) for these hot wort transfer and fermentation procedures.

- Purge both the wort and the fermentation vessel with carbon dioxide using either the line out on a corny keg or by using a sintered stone in other fermentation vessels.

- Pitch a pure culture of Lactobacillus or a Lactobacillus starter that is free of off-aromas.

- Maintain a fermentation temperature between 112° to 120° F. This can be achieved on the homebrew scale by the use of a ferm-wrap or other fermentation heating element and an insulated chamber such as a small chest freezer or a large insulated picnic cooler.

- As in previous methods, check the pH every 12 to 24 hours.

- When the desired pH is reached, cool the wort to the proper yeast pitching and fermentation temperature (between 45° to 55° F for lager Saccharomyces or between 65° to 75° F for ale Saccharomyces or Brettanomyces)

- Oxygenation at this point is very beneficial for the yeast and will not harm further Lactobacillus flavor development

- Pitch one or more Saccharomyces or Brettanomyces strains and proceed through a standard alcoholic fermentation from this point forward.

The ultimate goal of these three processes is the same: Produce a beer with a pleasant level of lactic acidity that is free of off-flavors in a short period of time. Lets now look at how to smell and taste the beer to detect the most common off-flavors that can arise from these fast souring methods.

Part 2 – Detecting Common Off-Flavors and Aromas and Understanding Their Cause.

As a brewer myself, it is always my goal to produce the best beer possible and it is from this perspective that I will launch into a discussion about off-flavors and aromas. That being said, I also know that, for many brewers who are first starting to experiment with sour beer, it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between “bad funk” and “good funk” in these beers.

In general, Lactobacillus in isolation (the goal of these methods) should produce a far simpler flavor profile than produced by either traditional brewers yeast or the common sour beer yeast Brettanomyces. The primary product of Lactobacillus is lactic acid, which is a simple organic acid with a soft pleasant sourness. Common foods that feature this acid include Greek yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and sourdough bread. For the candy fans, the addition of lactic acid is what differentiates “Sour Patch Kids Extreme” from the classic “Sour Patch Kids”.

In general, Lactobacillus in isolation (the goal of these methods) should produce a far simpler flavor profile than produced by either traditional brewers yeast or the common sour beer yeast Brettanomyces. The primary product of Lactobacillus is lactic acid, which is a simple organic acid with a soft pleasant sourness. Common foods that feature this acid include Greek yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and sourdough bread. For the candy fans, the addition of lactic acid is what differentiates “Sour Patch Kids Extreme” from the classic “Sour Patch Kids”.

The fermentation of Lactobacillus will also give its beers a fairly subtle yet classic mustiness. This can smell a bit like a damp basement or the forest after a rainstorm. Another aroma commonly associated with Lactobacillus is a floury smell associated with sourdough bread and sourdough starters. These are light aromas easily overpowered by other additions to the beer such as hops or fruit. Additionally, the aroma and flavor compounds produced by brewer’s yeast strains or Brettanomyces will easily mask these characteristics. Despite this, I believe it is the presence of these non-acidic characteristics that differentiate beers actually fermented with Lactobacillus from those that have simply received a large addition of food-grade lactic acid. In my opinion, this latter process creates an inferior product which tastes somehow artificial.

Lactobacillus beers, when smelled at room temperatures, should not “stink”. This is especially true after a primary fermentation by Saccharomyces or Brettanomyces. Immediately after the Lactobacillus fermentation, it is common for the wort to smell:

- Musty or Floury (This would be considered “good funk”)

- Sugary, Syrupy, & Sweet (Because Lactobacillus produces only a minute level of attenuation in comparison to yeast)

- A little Buttery (Occasionally, because certain strains of Lactobacillus can produce diacetyl in their fermentation)

Lactobacillus species are divided into two groups, homofermentative and heterofermentative. Homofermentative species will only produce lactic acid during their fermentations. Alternatively, heterofermentative species will primarily produce lactic acid but can also produce ethanol, carbon dioxide, and acetic acid during their fermentations. I bring this up because, in very low levels, this acetic acid will add flavor complexity and should not be considered an off-flavor when using these species / strains. On the other hand, if there is a strong and distinct aroma or flavor of vinegar, this would generally be considered undesirable and is likely due to contamination of the wort by Acetobacter or other unwanted aerobic microbes.

If using a clean ale strain such as White Labs WLP001, Wyeast 1056, or Safale US-05 to ferment your wort after souring with Lactobacillus, you would expect the fully attenuated beer to have only a slightly musty and fruity aroma, as well as a clean and simple sour flavor.

Lets now take a look at the aromas and flavors that we do not want to detect in either the wort or finished beer:

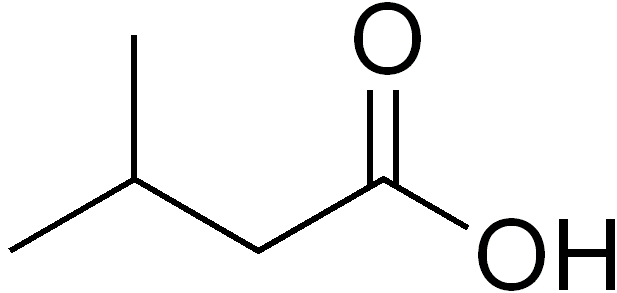

- Parmesan Cheese, Rancid Milk, or Stinky Feet (Isovaleric Acid)

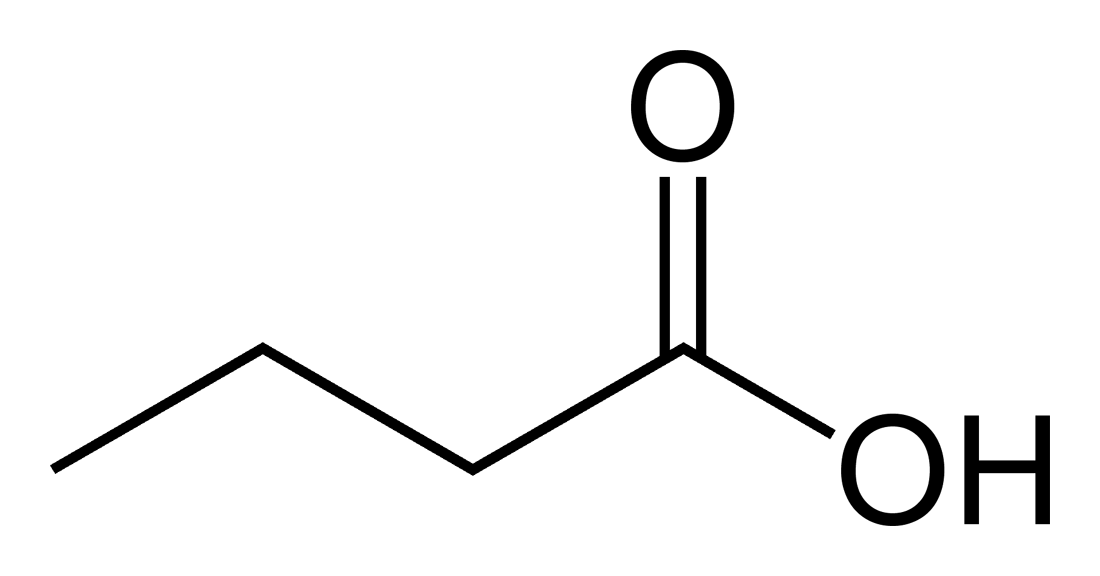

- Vomit or Bile (Butyric Acid)

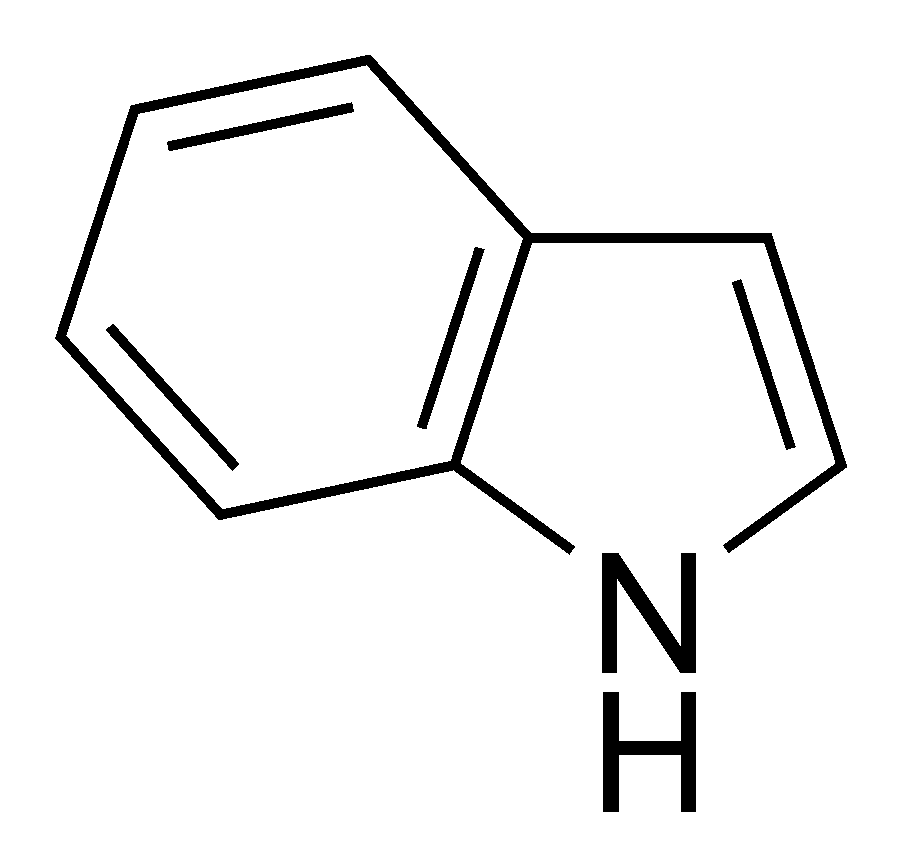

- Fecal, Manure, Poopy Diaper (Aromatic Indoles)

- A strong presence of Vinegar (Acetic Acid)

- Bandaid, Liquid Smoke, Medicinal (Phenolic Compounds)

These batches of sour red ale undergo a sour worting process before being pitched with Saccharomyces and Brettanomyces.

When I am brewing a batch of sour beer using a Lactobacillus-first fermentation, the presence of any of these characteristics in my beer would lead to the batch being dumped. This is because I am not willing to spend time aging a beer with off-flavors in the hope that they will eventually become better. While personally I’m not willing to age such batches, three of the chemical compounds that are listed above can be either reduced or turned into flavor positive compounds by the yeast Brettanomyces. These compounds include isovaleric acid, butyric acid, and certain phenolic compounds. If you detect these compounds in very low levels, aging with Brettanomyces can eliminate them over time. However, if any of these compounds are intensely strong, it is best to dump the batch and review your processes. A good rule of thumb would be that if a flavor or aroma is off-putting enough that you would not drink several pints of the beer, then save your efforts and dump it.

When tasting your beer for off-flavors, it is sometimes very useful to drink another commercial example of the style that is known to be free of defects. This side-by-side comparison can really help to highlight flavors in your beer that you may not have otherwise noticed. Additionally, because strong lactic acid can be overwhelming to some taster’s palates, it can be useful to adjust your palate to intense acidity before analyzing the flavors in your beer. This can be done with a favorite bottle of strongly sour beer, a glass of water blended with lemon-juice concentrate, or by eating a few sour candies like Sour Patch Kids or Warheads.

A few more general tips for tasting and smelling your beers include:

- Pour the beer into a tulip glass or other similar aroma-promoting glass.

- Smell and taste the beer when it is at cellar temperature and at room temperature. Tasting or smelling the beer at cold temperatures will mask or reduce many flavor and aroma compounds.

- When smelling the beer, don’t be afraid to get your nose deep in the glass and take several good whiffs in a row. If your nose needs a reset, smell the skin of your clean dry arm for several seconds.

- When tasting the beer, pull some air into your mouth with the sip. This helps to aerate the sample and bring out both flavor and aroma compounds.

- Avoid tasting the beer after smoking, chewing tobacco, or eating any strongly spiced or otherwise potently flavored foods.

- If you are hunting for subtleties, don’t be afraid to ask for help. Genetically we all have a very wide range of sensitivities to different chemical compounds. A group of good analytic tasters can be the most useful tool in a brewer’s arsenal.

At this point we have covered both the best-practices to be used while fast-souring with Lactobacillus and how to analyze our beers for both positive and negative results. For the practical brewer, you now have all the tools you need to go forth and brew delicious fast-soured beers. However, for the inquisitive brewers, I will now wrap up this article with a discussion of the science behind these practices.

Part 3 – Fast Souring Science

Before jumping into a discussion of the organisms responsible for producing off-flavors in these fermentations, I need to mention a caveat to this information: Sour mashing, sour kettling, and Lactobacillus-only fermentations are relatively recent products of the American craft brewing community. There have been no detailed scientific studies directly looking at the organisms that are in play when these processes fail. However we can make fairly educated guesses as to the identity of the organisms involved based upon the chemicals and off-flavors that they leave behind. Many of these organisms have been studied in other food products or in other processes related to industrial brewing (practically all well-funded beer science has been performed in the arena of industrial lager brewing). Deducing the identity of the organisms that commonly compete with Lactobacillus in these fermentations allows us to re-engineer the process to reduce or eliminate the risk of these unwanted microbes.

Butyric Acid Bacteria

The easiest of these organisms to identify are members of the Clostridium family. These bacteria, especially Clostridium butyricum, are well known in the brewing industry as producers of butyric acid due to their propensity to infect sugar syrups in bulk storage containers. Clostridium are obligate anaerobic (they cannot survive in the presence of oxygen), endospore forming, gram positive, rod shaped bacteria which metabolize simple sugars to produce butyric acid. Butyric acid both smells and tastes like vomit, bile, and rancid milk or cheeses. This chemical is present in low doses in goat and sheep milk, butter, and parmesan cheese. It is also present in human vomit.

Clostridium, and other less common butyric acid bacteria, while requiring the same oxygen free environment that Lactobacillus prefers, cannot tolerate the same pH and temperature ranges as Lactobacillus. While Lactobacillus can comfortably thrive between 115° and 120° F, Clostridium dies at temperature above 112° F. Additionally, while Lactobacillus purposely acidifies its environment in order to outcompete acid-intolerant bacteria, Clostridium prefers an optimum pH of 6.3. As the pH of its environment drops near 5.0, Clostridium loses its ability to produce butyric acid, and at a pH of 4.7 or below, these bacteria become completely inactivated. These tolerances produce our recommendations to always pre-acidify the wort to a pH of 4.5 and maintain a temperature above 112° F when possible.

Indole Producing Bacteria

The presence of fecal aromas or flavors in a sour beer are an indication of an infection by bacteria known as coliform bacteria. These bacteria include families such as Citrobacter, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Escherichia and are found throughout nature. One species, E. coli, is a common bacteria found in the large intestines of most humans. This species also garnishes media attention from time to time due to its occasional ability to become pathogenic and cause a toxic diarrhea. Many species of these bacteria metabolize various amino acids to produce the chemical indole, a chemical which smells strongly of feces. These bacteria are rod shaped facultative anaerobes (preferring oxygen free environments but able to survive in its presence), which do not form spores. Certain groups of these bacteria can survive at temperatures above those preferred by Lactobacillus. Luckily for use, these bacteria, while able to survive a low pH environment, do not reproduce or metabolize well as the pH approaches 4.4. Therefore, our recommendation of lowering the pH to 4.5 before fermentation will help to prevent these bacteria from producing off-flavors in our fermentations.

Bacterial Production of Isovaleric Acid

Unfortunately, this narrative becomes more complicated when we look at bacterial sources for isovaleric acid. One definitive source of this off-flavor is metabolism of the amino acid leucine by a bacterium called Bacillus subtilis. This bacterium is present on human skin and is responsible, in part, for the production of foot odor. This rod shaped bacteria is known for its ability to form a protective endosperm which allows it to survive a wide range of environmental conditions. Luckily, this bacteria is an obligate aerobe (requiring oxygen to survive) and therefore can be prevented from affecting our sour fermentations when we maintain an oxygen free environment.

A second, and less controllable source of this off-flavor may be an interaction between a bacteria commonly found in yogurt cultures, Streptococcus thermophilus, and the very Lactobacillus which we are utilizing in our souring fermentations. Lactobacillus, in isolation, does not possess the metabolic enzymes needed to convert leucine into isovaleric acid. However, it seems that when S. thermophilus is present, it can potentially supply Lactobacillus with the chemical intermediates needed to perform this metabolism. The bad news regarding this interaction is the fact that S. thermophilus thrives in all of the same environmental conditions as Lactobacillus. Therefore the only process control that can prevent its influence in our sour fermentations is the use of good sanitation practices.

When working with wild harvested Lactobacillus, its always a good idea to test your results first using small starter batches.

This potential interaction is one of the reasons why I strongly prefer to use only pure cultures of Lactobacillus or starters which have already proven to be free of off-flavors. The temperatures of mashing will generally sanitize our wort and the process of boiling definitely will. (2015 Update: Always perform at least a 15 minute boil before beginning a fast souring process) As long as from these points forward only known cultures are introduced, there will be little to no risk of contamination. In fact, while I have used Lactobacillus first fermentations dozens of times, I have never experienced any of these common off-flavors in my beers.

Another reason to consider only using known cultures is the fact that bacteria can and do frequently swap genetic material, allowing certain strains to develop properties that they previously lacked. Therefore, the only way we can ever really know what is fermenting in our beers is to ensure that we put only the bacteria that we want into them. With that said, following the best practices outlined here will almost certainly yield positive results in your breweries.

Hopefully, this review has been interesting, informative, and helpful to brewers looking to develop a quick and simple acidity in their beers. These processes alone work very well when producing styles like Berliner Weisse and Gose, and can be very useful for establishing a baseline acidity in other more complex styles as well. As always, please email me at matt@sourbeerblog.com with any questions.

Have fun and brew sour!

Cheers!

Matt “Dr. Lambic” Miller

November 2015 Update: For those looking to expand their fast souring knowledge with techniques such as Lactobacillus pitch rate, starters, and recipe design, check out our new follow up article: Lactobacillus 2.0 – Advanced Techniques for Fast Souring Beer!

References:

Ghoddusi, Hamid B., Richard E. Sherburn, and Olusimbo O. Aboaba. “Growth Limiting PH, Water Activity, and Temperature for Neurotoxigenic Strains of Clostridium Butyricum.” ISRN Microbiology2013 (2013): 1-6. Web.

Goodwin, Jay, and Scott Moskowitz. “The Sour Hour / Episode 4.” The Sour Hour. The Brewing Network. Concord, CA, 20 Nov. 2014. Radio. (Features guest brewer Khris Johnson of Green Bench Brewing in St. Petersburg, Florida. Khris is the first brewer that I’ve heard make the direct connection between certain sour mash/sour kettle off-flavors and isovaleric acid)

Helinck, S., D. Le Bars, D. Moreau, and M. Yvon. “Ability of Thermophilic Lactic Acid Bacteria To Produce Aroma Compounds from Amino Acids.”Applied and Environmental Microbiology 70.7 (2004): 3855-861. Web.

Klocker, Alb. Fermentation Organisms; a Laboratory Handbook. London: Longmans, Green, 1903. Print.

Sakamoto, Kanta, and Wil N. Konings. “Beer Spoilage Bacteria and Hop Resistance.” International Journal of Food Microbiology 89.2-3 (2003): 105-24. Web.

Vriesekoop, Frank, Moritz Krahl, Barry Hucker, and Garry Menz. “125Anniversary Review: Bacteria in Brewing: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.” Journal of the Institute of Brewing 118.4 (2012): 335-45. Web.

Zhang, Chunhui, Hua Yang, Fangxiao Yang, and Yujiu Ma. “Current Progress on Butyric Acid Production by Fermentation.” Current Microbiology59.6 (2009): 656-63. Web.

Zigová, J., and E. Šturdík. “Advances in Biotechnological Production of Butyric Acid.” Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology24.3 (2000): 153-60. Web.