Hello Sour Brewers!

Last December when I published our article on Fast Souring with Lactobacillus, I had hoped that it would provide a useful overview to both hobby and commercial brewers interested in using sour mashing, kettling, or worting techniques. Personally, I have been blown away by the positive response that I have received from this article, which even now continues to be the most read, commented upon, and cited resource on the blog! I believe that this success is due to both the dramatic explosion in popularity of the Gose and Berliner Weisse styles of sour beer as well as the proliferation of sour brewers within the worldwide homebrewing community.

Over the past year, I have also received numerous emails from folks who have had their Lactobacillus-first beers go awry in one way or another. I love it when both sour beer fans and brewers contact me because it gives me the opportunity not only to teach, but also to learn from other’s experiences. I have seen trends in both questions and troubleshooting help which have led me to believe that the time has come to write a follow-up article to Fast Souring with Lactobacillus. I hope that it is both educational and useful!

Lactobacillus 2.0

or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Sours

Advanced Techniques for Fast Souring Beer

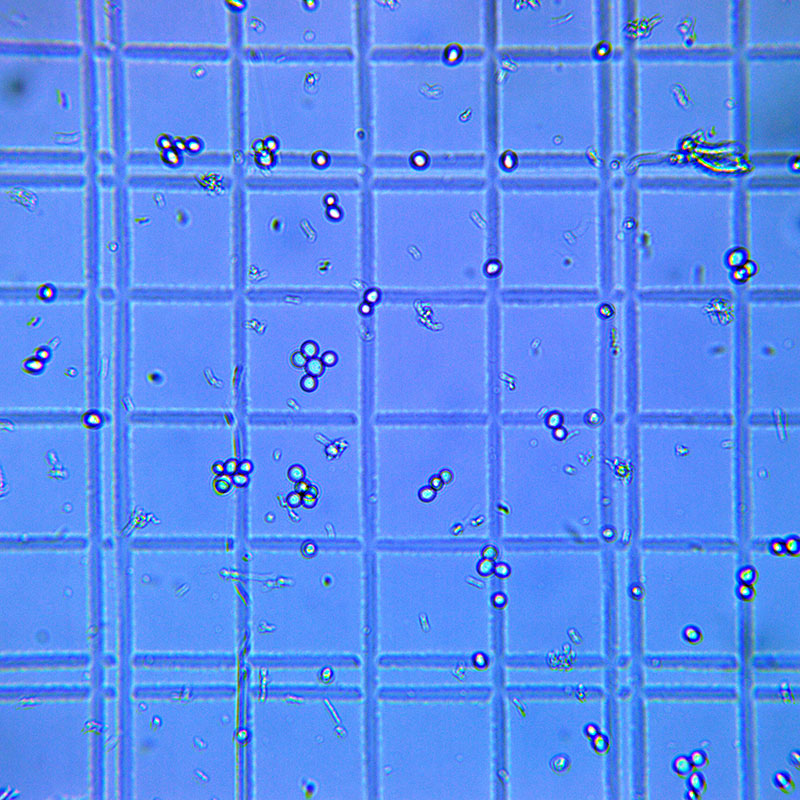

In Fast Souring with Lactobacillus, I discussed three major ways to quickly sour wort before a primary fermentation with yeast. In this article, I am going to narrow this down to a single sour brewing pipeline with a few variable options depending upon your goals for the final beer. This simplified souring pipeline is designed to give brewers a repeatable process by which to create quickly soured beers while both avoiding major problem areas encountered with previously discussed methods as well as optimizing the fermentation profile and flavors produced by various known strains of Lactobacillus. This process is visualized in the following flow chart:

At this point you may be noticing that, in all paths, the beer is boiled before adding Lactobacillus. Many brewers may be asking: Why do I need to do this? Don’t mash temperatures pasteurize the wort?

It turns out that in many cases, mash temperatures are not enough to fully sanitize wort. The strongest trend I have seen in all of the troubleshooting emails I receive is this: Beers that don’t receive at least a short boil before souring undergo far more problematic fermentations. In most cases, the preventative measures discussed in the previous article (temperatures above 115° F, pre-acidification to pH 4.5, and avoidance of oxygen) will prevent unwanted bacterial fermentations. However, these steps do not prevent unwanted fermentation by wild yeasts and this turns out to be a frequent problem. When beer is neither boiled before souring nor are these protective steps in place, any host of problems, infections, and off-flavors can arise.

This is a major change from advice given previously both here and by many other sources. The previous advice was based upon a standard concept called “Vat Pasteurization” which is typically applied in the milk processing industry. Research into milk pasteurization has found that large volumes of milk held at or above 145° F for at least 30 minutes will be sanitized. While typical mashes meet these time and temperature requirements, experimental testing and the experience of numerous brewers indicates that mashing alone is simply not enough to sanitize wort. Theories which may explain why this is the case include:

- Wort chemistry and the physical dynamics of the grain / water mixture may provide some form of protection to microorganisms against inactivation by standard mash temperatures.

- Small pockets of the mash and / or potential “dough balls” within the mash may never actually reach the temperatures needed for pasteurization to occur

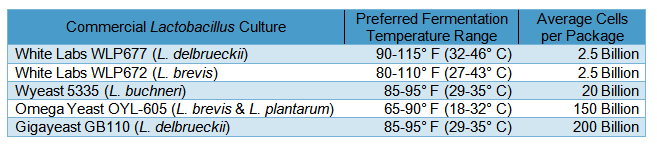

A second major change is the recommendation to target temperatures during the Lactobacillus fermentation that may be lower than 115° F. In our previous article this temperature was recommended to discourage contamination by bacteria of the Clostridium genus. While I still advise using this temperature for “wild” Lactobacilli originating from inoculation by grain or other unknown origins, there are several lab cultured strains available that will not acidify the wort properly at 115° F. I have compiled a chart to help brewer’s target a temperature which will yield a fast souring of their wort based on the preferred fermentation environment of the Lactobacillus strains listed. Keep in mind that, when using some of these strains, we will lose the protective factor of high temperature and therefore both sanitation and the other precautionary methods available will become even more important to avoiding the off-flavors of contamination.

It is important to remember that when Lactobacilli are creating lactic acid, they are doing so as a part of their normal metabolic growth and survival functions much in the same way that yeast do so when producing alcohol and CO2. While it is rarely discussed, this means that pitching rate is something that we need to consider. This is especially true when trying to troubleshoot a Lactobacillus fermentation that did not get sour enough or took longer than desired to get sour.

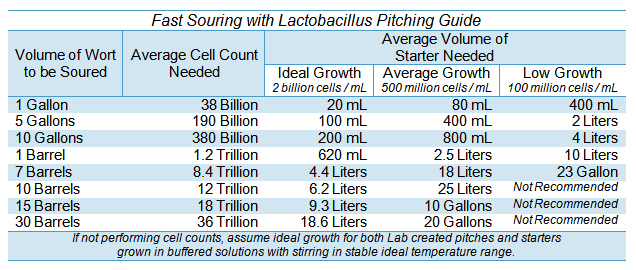

Lactobacillus Pitching Rates

There are two methods that can be used to ensure that we have an adequate pitch of Lactobacillus. The first of these methods bases the pitch rate on estimated cell counts per mL of wort. The second method is based on the volume of starter wort created and assumes that the Lactobacillus culture will reach a maximum cell density within that wort somewhere between 15 and 30 hours after pitching. I am comfortable recommending either technique because, when you crunch the numbers, both methods come out to yield approximately the same results.

Pitching Based on Cell Count:

When calculating the amount of Lactobacillus to pitch, about 10 million Lactobacillus cells per mL of wort are required to sour a beer within 24 to 48 hours depending on the species or strains being used. This general rule was derived experimentally at the Gigayeast laboratory after testing a number of Lactobacillus strains under a variety of conditions. This estimate also very closely matches my own experimental observations of beers that have successfully soured quickly in my brewery. My observations have suggested that the pitch rate for Lactobacillus should match the traditional pitch rate quoted for ale strains of Saccharomyces: 1 million cells per mL of wort per degree Plato.

Pitching Based on Volume:

The second method for pitching Lactobacillus is recommended by Lance Shaner of Omega Yeast Labs. This method is based upon using Omega Yeast’s Lactobacillus Blend and involves the creation of a one liter starter for 24 hours before pitching. Lance has found that this one liter starter will typically be effective in creating robust acidification of up to 2 barrels (62 US gallons) of wort within 24 hours.

A number of studies have found that when Lactobacilli are cultured in the lab using MRS media or other similarly buffered nutrient solutions, they can reach a maximum cell density of nearly 9 billion cells per mL of solution. However, the studies I reviewed also indicated that under non-ideal conditions (like in the starters we are capable of producing), the cell density of a solution would more realistically reach between 2 to 5 billion cells per mL. If you assume that the average Lactobacillus starter will reach a peak cell density of about 2 billion cells per mL within 24 hours, that yields a theoretical pitch rate of 8.5 million cells per mL when pitched into 2 barrels of wort. This estimate provides some theoretical validity to the idea that either method can be an effective way to ensure that enough Lactobacilli are pitched into a wort to ensure fast souring.

Now that we know how to determine approximately how much Lactobacillus we will need to pitch for fast souring, let’s take a look at how to create starters to grow these amounts:

Lactobacillus Starters

Earlier this year, Samuel Aeschlimann of Eureka Brewing ran a series of experiments which compared a number of traditional and modified starter solutions in order to determine whether any of them could yield Lactobacillus growth rates similar to those that occur in MRS media. My recommendations here are based upon Sam’s formula with a minor tweak in sugar composition based upon my own research. The goal of this starter recipe is to provide:

- The nitrogen and inorganic nutrients required for optimal growth

- A sugar composition of 2 to 3% w/v glucose, which has been shown to be optimal in stimulating Lactobacillus growth and metabolism.

- Enough buffering capacity to prevent the Lactobacillus from slowing their own growth via an over-acidification of their environment.

To create a starter optimized to grow Lactobacillus, combine the following ingredients per Liter of wort and boil for 15 minutes:

- 90 grams Dry Malt Extract

- 20 grams Dextrose (Glucose) (sold to brewers as corn sugar)

- 20 grams Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3 / chalk)

- 1 gram Yeast Nutrient or DAP (diammonium phosphate)

Cool this starter solution down to the temperature preferred by the strain of Lactobacillus that you are culturing and maintain this temperature as best as possible for 24 to 36 hours. You want to seal the flask with a rubber stopper and airlock to prevent additional oxygen from entering the starter solution. I would recommend using a stir plate set on a low rotation. This low setting will help to encourage growth by increasing microbial access to nutrients as well as aiding in the removal of CO2 for heterofermentative strains. It is best to time your starter’s creation so that it can be pitched into the wort you intend to sour between 24 to 48 hours after making the starter. However, if this is not possible, follow the same guidelines that you would for yeast starters: Store the unused starter under refrigeration and use within one week’s time to maintain high viability.

Lactobacilli do not quickly flocculate after fermentation in the same way that many strains of brewer’s yeast can. This means that to ensure fast souring you will need to pitch the entire starter volume into the wort. One caveat here is to decant the starter wort off of any chalk sediment at the bottom of the flask. Not all of the calcium carbonate will always enter solution in the starter and we do not want to pour this into the beer if we can avoid it.

When creating starters, any fresh single pitch of a commercial strain will provide ample initial Lactobacilli cells to produce an effective starter within 24 to 36 hours, this includes single White Labs vials which contain approximately 1.8 to 2.7 billion cells per tube. One practical way to ensure that your starter culture is multiplying as expected is to monitor for turbidity changes. Much like yeast starters, Lactobacillus starters will become increasingly cloudy as the cell density rises.

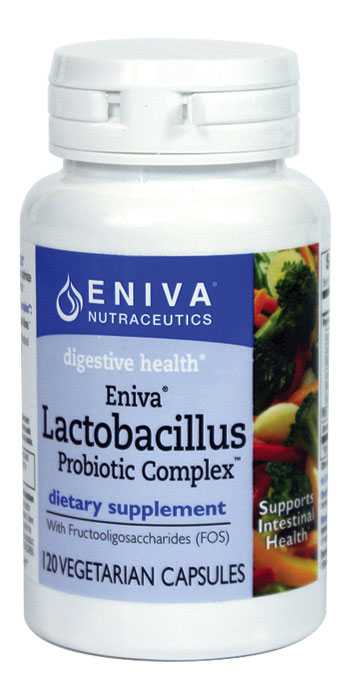

Recently, many home and craft brewers have begun experimenting with the wide variety of Lactobacillus strains or blends sold in health food stores as digestive probiotics. These cultures are not only cheap and easy to find, but also provide a wider variety of potential flavor subtleties when used in the fast souring process. If using liquid probiotics, you can use the cell estimates on the packaging to determine whether a starter will be needed. When in doubt, go with the starter. If using freeze-dried (lyophilized) probiotics (capsule forms), it is best to open up the capsules and rehydrate the powdered Lactobacilli inside using distilled water in the same way that dry-yeast packages should be rehydrated. After rehydration, I would recommend adding this slurry to a starter to ensure a healthy and adequately sized pitch.

Recently, many home and craft brewers have begun experimenting with the wide variety of Lactobacillus strains or blends sold in health food stores as digestive probiotics. These cultures are not only cheap and easy to find, but also provide a wider variety of potential flavor subtleties when used in the fast souring process. If using liquid probiotics, you can use the cell estimates on the packaging to determine whether a starter will be needed. When in doubt, go with the starter. If using freeze-dried (lyophilized) probiotics (capsule forms), it is best to open up the capsules and rehydrate the powdered Lactobacilli inside using distilled water in the same way that dry-yeast packages should be rehydrated. After rehydration, I would recommend adding this slurry to a starter to ensure a healthy and adequately sized pitch.

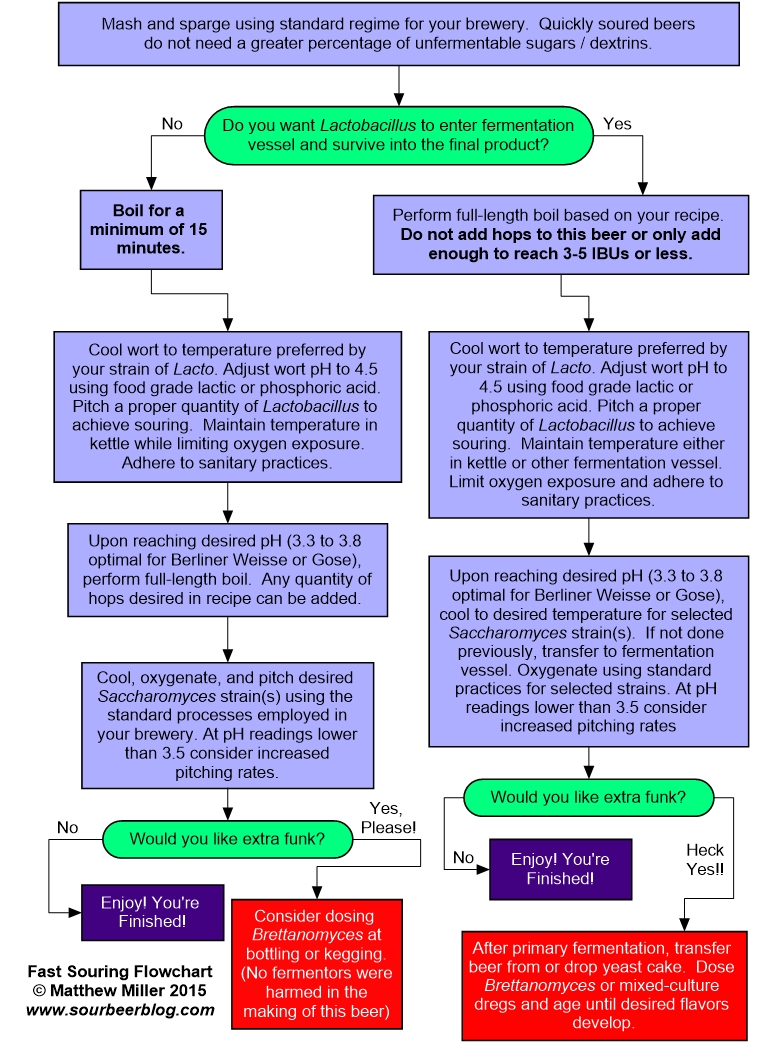

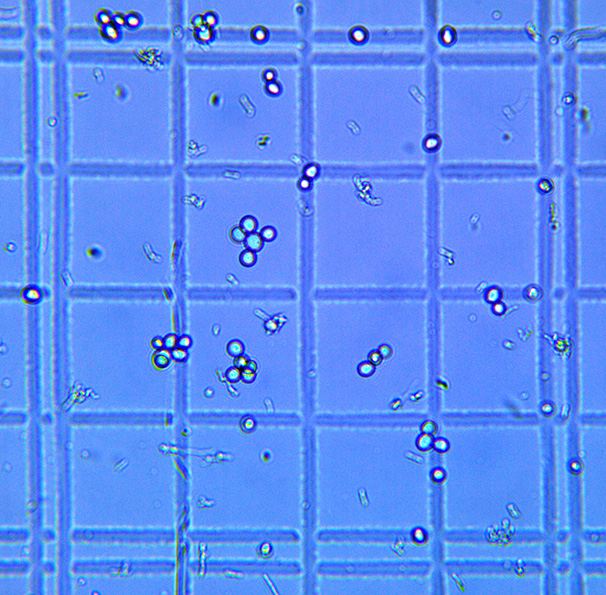

A microscopic view of both Saccharomyces (large round cells) and Lactobacillus (small rod shaped cells) in one of the author’s fast souring beers. After acidification to pH 3.45, this beer was fermented with WLP001, blended with fresh mangos, and dry hopped using galaxy hops.

While both cell count estimates and starter volume estimates can be used to successfully ensure that enough Lactobacilli are pitched for fast souring, most brewers will find pitching based on volume to be more practical. Lactobacillus cells are much smaller than yeast cells and therefore they are more difficult to accurately count under a microscope. Additionally, different species and strains of Lactobacillus will grow to differing cell densities and at differing rates. Therefore, it is best to err on the side of caution. We want to ensure that we pitch enough cells to ensure fast souring, but over-pitching of Lactobacillus tends not to cause any significant problems for the brewer. Luckily, this is because, in our unbuffered worts, the growth and souring potential of Lactobacillus is a self-limiting process that will generally bottom out somewhere at or above a pH range of 3.0 to 3.4. If the lower portion of this range is more acidic than you would like to target, simply make sure to closely monitor your pH and end the souring process as discussed above when you reach the desired pH level.

I have created the following table based upon the minimum pitch rates for the volumes of beer listed, but, if in doubt, pitch more.

Recipe Design and Process Considerations

It is important to remember that a beer’s recipe, wort production, and fermentation conditions are all important considerations in the fast souring process. Starting with the mash, a beer’s ability to be soured quickly can be enhanced by producing a more fermentable wort through the targeting of lower mash saccharification temperatures. This is because most strains of Lactobacillus will preferentially consume the simplest sugars available, and these sugars tend to be formed in higher proportions at lower mash temperatures.

The IBU level of a beer is such an important consideration when fast souring that I chose to mention it directly in the flowchart above. Nearly all commercial strains of Lactobacillus are extremely sensitive to hops. Even the more “hop tolerant” strains such at L. brevis tend to lose their ability to significantly acidify beers with an IBU level of 5 or greater. Luckily, as seen above, brewers can easily add hops to a beer by boiling after it has been soured. Alternatively, dry-hopping is an excellent option for adding hop character to a mature sour beer.

Original gravity (and associated final ABV) is another important factor to consider when designing a beer to be fast soured. Any beer with an original gravity higher than 1.040 SG (10 Plato) will be soured more slowly or incompletely by Lactobacillus. When designing higher ABV sour beers, plan to allow the Lactobacillus to survive into the fermentation / aging vessel so that it can continue to slowly acidify the beer over a period of several months.

Quality Control

While I wrote extensively about this topic in the article Fast Souring With Lactobacillus, it is such an important concept that it bears repeating. Lactobacillus-only fermentations should not smell like vomit, bile, parmesan cheese, stinky feet, or feces. The presence of any of these aromas before the addition of Saccharomyces or Brettanomyces is an indication of infection by an unwanted species of bacteria such as Clostridium butyricum. Additionally, medicinal, plastic, smoky, or phenolic aromas or flavors are undesired and are an indication of infection by a strain of wild yeast.

It is normal for Lactobacillus acidified wort to smell sweet, bready, doughy, musty, buttery, vegetal, or reminiscent of sauerkraut. These aromas are due to byproducts of heterofermentative fermentation by Lactobacillus such as diacetyl and acetaldehyde. Some of the characteristic doughy and musty aromas may persist into the final beer, but any potential sweet, vegetal, buttery, and sauerkraut aromas will generally be gone after fermentation by Saccharomyces or Brettanomyces.

Many of the commercially available strains of Lactobacillus can undergo heterofermentative fermentation, meaning that in addition to producing lactic acid, they can also produce alcohol and carbon dioxide. This fact has led many brewers to assume that these strains will sometimes nearly or fully ferment their wort before the addition of brewer’s yeast. While heterofermentative strains can slightly begin to attenuate a beer, a drop of greater than 8 points of specific gravity (2 points Plato) within 24 to 48 hours is almost always a sign of yeast contamination. Such contamination may not negatively impact the beer in regard to off-flavor production, but it may reduce the souring potential of the Lactobacillus through competition for simple sugars.

Ending Thoughts

It is an exciting time for sour beer fans both in the United States and abroad. Worldwide, a greater number of craft brewers and homebrewers are beginning to experiment with sour beer styles than ever before. The ability to create flavorful sour beers both quickly and cost-effectively is a valuable tool for the versatile brewer. It is my hope that this article, when read in tandem with Fast Souring with Lactobacillus, will provide both home and craft brewers with a well-rounded understanding of how to produce delicious sour beers quickly while maintaining a high degree of quality.

Cheers and Happy Brewing!

Matt “Dr. Lambic” Miller

References:

Aeschlimann, Samuel. “Evaluate Starter Media to Propagate Lactobacillus Sp.” Eureka Brewing. N.p., 18 May 2015. Web. 18 Nov. 2015.

Carey, Erin. “Using Calculus to Model the Growth of L. Plantarum Bacteria.” Undergraduate Journal of Mathematical Modeling: One Two UJMM: One Two 1.2 (2013): n. pag. Web.

Gu, SP, Z. Liu, and PZ Song. “The Measurement of Growth Curve and Generation Time of Lactobacillus.” Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue 7.4 (1998): 226-27. Print.

“Lactobacillus.” Milk The Funk Wiki. Web. 18 Nov. 2015.

LACTOBACILLI MRS BROTH. Lansing, MI: Neogen Corporation, Nov. 2010. PDF.

Siegrist, Jvo. “Lactobacilli.” Sigma-Aldrich. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2015.

Tonsmeire, Michael. American Sour Beers: Innovative Techniques for Mixed Fermentations. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications, 2014. Print.

Zacharof, MP; Lovitt, RW and Ratanapongleka, K. Optimization of Growth Conditions for Intensive Propagation, Growth Development and Lactic Acid Production of Selected Strains of ‘Lactobacilli’ [online]. In: Engineering Our Future: Are We up to the Challenge?: 27 – 30 September 2009, Burswood Entertainment Complex. Barton, ACT: Engineers Australia, 2009: [1830]-[1838]. ISBN: 9780858259225. [cited 18 Nov 15].

Valík, Ľubomír, Alžbeta Medveďová, Michal Čižniar, and Denisa Liptáková. “Evaluation of Temperature Effect on Growth Rate of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG in Milk Using Secondary Models.” Chemical Papers 67.7 (2013): n. pag. Web.

Xiong, Tao, Xuhui Huang, Jinging Huang, Suhua Song, Chao Feng, and Mingyong Xie. “High-density Cultivation of Lactobacillus Plantarum NCU116 in an Ammonium and Glucose Fed-batch System.” African Journal of Biotechnology 10.38 (2001): 7518-525. Print.