Howdy Sour Beer Fans!

Funky and sour beers have been gaining momentum for quite some time now. But for all the barrel aged sours and delicious Brettanomyces laced saisons: where have all the Berliner Weisses gone? To my surprise there are less than twenty widely available American commercial examples of this classic style, such as The Bruery’s Hottenroth, White Birch’s Berliner Weisse and Nodding Head’s Berliner Weisse.

That’s surprisingly low when compared to the plethora of more esoteric styles of sour beer widely available. More shocking (well, not too shocking considering the Germans have adopted lager as the core of their beer consumption) is that I can only find three German breweries that still produce this classic wheat-based sour beer: Berliner Kindl Brauerei, Gasthaus & Gosebrauerei Bayerischer Bahnhof, and Professor Fritz Briem. While it is hard to find examples from these breweries (Professor Fritz Briem 1809 Berliner Weisse is the only one that I’ve personally ever come across, and to be honest, it was a tad old), this is a style that’s super easy to brew, so you can have freshies all the time. So with that, let’s get lactic!

The history of this once booming style is a bit of a mystery. The original versions of Berliner Weisse were thought to be influenced from a style of Broyhan beer, named after Cord Broyhan, the brewer who concocted this wheat based brew in 1526. Over time, the style evolved into the tart, dry, and effervescent wheat beer we know today. Even Napoleon Bonaparte was touting Berliner Weisse as the “Champagne of the North”, but then, just as fast as those 700 German breweries were pumping it out, the style went the way of the dinosaurs. If I had to fancy a guess as to what led to the demise of Berliner Weisse, I would say it was the growing popularity of all those clean and delicious pale lagers throughout the region which eventually pushed out the tart and refreshing brew. Luckily for us, Berliner Weisse has made a steady comeback over the last half a decade thanks to both home brewers and the unquenched thirst of the American sour beer drinking population.

Style Overview

So what is a Berliner Weisse anyway? Well, I’m glad you asked, because it is a relatively simple, low ABV, pale wheat beer with a tart and clean lactic sourness. A majority of the flavor and aroma come from the malt bill. Flavors of crisp crackers, biscuit, wheat, and dough round out a pleasant lemony lactic sourness and light to moderate bouquet of fruity esters. When designing a recipe, you’re looking to create a session strength ale, anywhere from 2.8 to 3.8 ABV is appropriate. Any hop aroma is out of place in a classic example and hop bitterness, while appropriate, should be just barely present at a minimal 3 to 8 IBUs. (Don’t forget that hops inhibit Lactobacillus, so we highly encourage you to sour before the addition of hops to your process).

So what is a Berliner Weisse anyway? Well, I’m glad you asked, because it is a relatively simple, low ABV, pale wheat beer with a tart and clean lactic sourness. A majority of the flavor and aroma come from the malt bill. Flavors of crisp crackers, biscuit, wheat, and dough round out a pleasant lemony lactic sourness and light to moderate bouquet of fruity esters. When designing a recipe, you’re looking to create a session strength ale, anywhere from 2.8 to 3.8 ABV is appropriate. Any hop aroma is out of place in a classic example and hop bitterness, while appropriate, should be just barely present at a minimal 3 to 8 IBUs. (Don’t forget that hops inhibit Lactobacillus, so we highly encourage you to sour before the addition of hops to your process).

While I’m sure that Brettanomyces was commonly present in historic examples of the style, modern versions of the style typically portray little to no overt Brett character. Rather, these beers showcase a clean fermentation profile with a neutral yeast like German Ale Yeast from White Labs or Wyeast. Additionally the use of California Ale or other low-impact yeast strains is acceptable, just be sure to take care in selecting a strain that doesn’t produce much sulfur, or any significant phenols, as either will put you out of style. When serving these beers, it is traditional to carbonate to a high level, anywhere from 2.5 to 3.5 volumes of CO2 is appropriate.

In Germany, its uncharacteristic to drink the style by itself, it is much more commonly served with a light shot of raspberry or woodruff syrup to tone down the beer’s acidity. Most American sour fans (including us), prefer the style straight, or with fruit additions during fermentation in order to add complexity but maintain the tart and refreshing bite that we love in the beer.

Recipe Design

When deciding what malts to use be sure to keep it simple! In my opinion, the use of pilsner and wheat malts is the key to nailing this style. Not to say you couldn’t use other English or American pale malts, but you’d miss out on the delightful biscuit and cracker flavors that are showcased by Pilsen malt. The use of crystal malts (or really any specialty malts) is not encouraged since we are looking for a pale, crisp, and dry beer.

When deciding what malts to use be sure to keep it simple! In my opinion, the use of pilsner and wheat malts is the key to nailing this style. Not to say you couldn’t use other English or American pale malts, but you’d miss out on the delightful biscuit and cracker flavors that are showcased by Pilsen malt. The use of crystal malts (or really any specialty malts) is not encouraged since we are looking for a pale, crisp, and dry beer.

Another ingredient: hops, have an incredible influence over the outcome of your Berliner Weisses… most importantly not over hopping! Low-alpha German varietals such as Tettnang, Saaz, Hallertauer, and Spalt are classics, although I think using a tiny charge of Magnum works well also. Any American hops that show-off bold aromas of citrus, tropical fruits, or pine are out of style. We have found that Crystal, a low-alpha American hop, also plays nicely in these beers.

Methods of souring can vary significantly based on your equipment setup and needs. I will outline two classic ways to achieve the desired level of sourness without making something either completely lackluster or a full-on acid beer. First, let’s talk about acceptable levels of lactic acid. I like to shoot for a pH range of 3.3-3.7. Berliner Weisse shouldn’t be an enamel remover. Its tartness should complement the doughy, cracker and biscuit flavors, not steamroll over them. Likewise, for most palates, if the acidity is so strong that it’s impossible to detect the light bittering, its likely too sour.

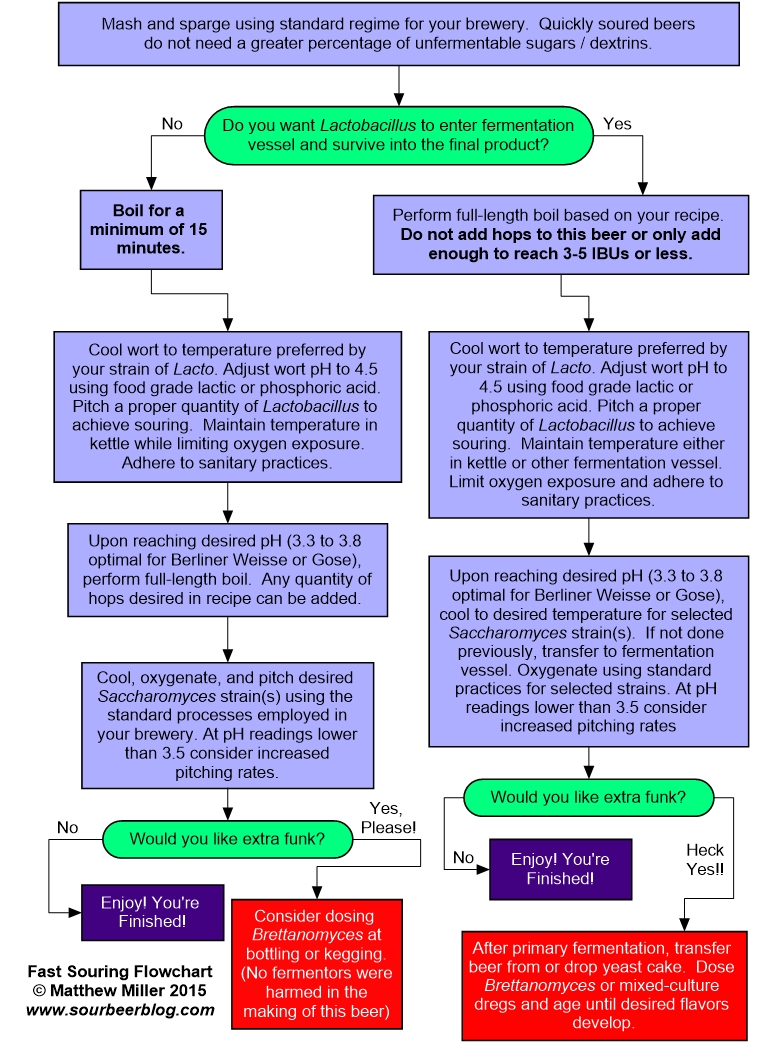

Both of our methods are going to assume that at some point in the process you do want to include hops into the beer. If you are going for an un-hopped freestyle sour (or a dry-hopped sour), then technically you aren’t making a Berliner Weisse. So for the purposes of this article, I’m going to skip that concept. This really leaves a brewer with two options for souring the beer: either before or after the inclusion of hops in the boil.

Let’s start with the process that’s more difficult to pull-off successfully: souring after the hops have been added. To do this you’ll be mashing and boiling your Berliner recipe just like any other beer. In this process it is absolutely critical that the IBUs are low. We say 3 to 8, but staying at the lower end of this spectrum will dramatically increase your likelihood of achieving a beer with the acidity you want. After your wort is cooled to pitching temperature you can either fast-sour the wort by adding Lactobacillus first or you can co-pitch your Lactobacillus and Saccharomyces strains. The keys to making this approach work are:

- Selecting the right Lactobacillus L. plantarum (while a souring monster) is essentially completely hop intolerant. This is the same case with practically any pro-biotic based Lactobacillus blends. You are more likely to achieve success with large pitches of L. delbrueckii or L. brevis.

- Pitching the right cell counts. If pitching Lactobacillus alone, you want to shoot for around 1 million cells per mL per degree Plato (aka. classic ale yeast pitch rates). If co-pitching with an ale yeast, you want to pitch 5 times more Lactobacillus than Saccharomyces based on cell count. To learn how to create Lacto starters, click here.

- Giving the beer ample time. With hops present, your Lactobacillus will be fighting an uphill battle. Expect longer than average times for souring.

The second option: souring before the addition of hops, is our preferred method for producing Berliner Weisses at Sour Beer Blog. This method is outlined in detail in our Fast Souring Flowchart in this article. When carried out successfully, this process allows you to quickly sour your wort within a timeframe of 24 to 48 hours, then boil it a second time allowing you to add the desired level of hops to the beer. A benefit of this method, that is particularly applicable to Berliner Weisse production, is the fact that the second boil will also volatize away a number of slightly-off flavors and aromas produced by Lactobacillus fermentation. While a healthy Saccharomyces ferment will help to clean up these flavors as well, the second boil does a great job of producing a truly clean and crisp Berliner Weisse.

Here is the process we use to produce our classic Berliner Weisse:

- Grist: 40% White Wheat Malt, 30% Bohemian Pilsner Malt, 30% Maris Otter.

- Brewing Water: Reverse Osmosis H2O with 1 ml of 10% phosphoric acid per gallon to all water used. ½ teaspoonful of calcium chloride and ½ teaspoon of calcium sulfate added to the mash per 5 gallons of finished beer.

- Step Mash: 15 minutes at 130° F, 60 minutes at 155° F, then 5 minutes at 168° F. Fly sparge until you reach a pre-boil gravity of 1.051

- Boil wort for 15+ minutes, then cool to 95° F and transfer into Lactobacillus fermentation vessel, or leave in kettle if kettle souring. Because we ferment in Sankey kegs, we do not cool the wort at all. We transfer the boiling wort into the stainless steel kegs (with serving tubes removed) and cover the openings with aluminum foil. These are then allowed to slowly cool to 95 F over the next 12 to 24 hours. This completely pasteurizes the fermentation vessels and allows us to use single strain Lactobacillus souring without fear of contamination. As an additional precaution, it is recommended to pre-acidify the wort to pH 4.5 with lactic acid, although we often skip this step because we are confident in the pasteurization of our wort and in our sanitary handling procedures.

Pitch an appropriately sized Lactobacillus culture of your choosing. Hold at the preferred temperature for that strain until you reach your desired pH. For our recipe, we use the probiotic drink Goodbelly, at a rate of 1 carton per 12 gallons of wort, and we allow the wort to acidify to a pH of 3.45 to 3.5, which takes approximately 36 hours.

Pitch an appropriately sized Lactobacillus culture of your choosing. Hold at the preferred temperature for that strain until you reach your desired pH. For our recipe, we use the probiotic drink Goodbelly, at a rate of 1 carton per 12 gallons of wort, and we allow the wort to acidify to a pH of 3.45 to 3.5, which takes approximately 36 hours.- Transfer wort back to boil kettle or re-fire kettle with souring wort already inside.

- After souring, the gravity should be essentially unchanged. Our most recent batch dropped from 1.051 to 1.050.

- Boil for 90 minutes. Add US Crystal hops at 30 minutes targeting 8 IBUs.

- At end of boil, dilute using R.O. H2O to a starting gravity of 1.035 (this can be done earlier in the boil if contamination is a concern). It is interesting to note that diluting with pure water will not change the pH of your wort.

Cool wort to 65° F, oxygenate, and pitch healthy starter of German Ale / Kolsch yeast at an appropriate cell count. We used a slurry created by pitching 2 White Labs Pure Pitch packs into a 4.5 liter starter.

Cool wort to 65° F, oxygenate, and pitch healthy starter of German Ale / Kolsch yeast at an appropriate cell count. We used a slurry created by pitching 2 White Labs Pure Pitch packs into a 4.5 liter starter.- Ferment at 65° F for 5 to 7 days.

- Cold crash to 50° F for 2 days, then keg, carbonate, and enjoy!

- The final beer should reach a final gravity of around 1.006 (82.4% attenuation, 3.8% ABV) and have a final pH in the 3.25 to 3.35 range.

Serving a Berliner Weisse

Carbonation is an important consideration when dialing in a classic Berliner Weisse. I would shoot for 2.8 to 3.5 volumes to keep it nice and spritzy. At serving time, the use of syrups: both woodruff and raspberry are the traditional choices. But I encourage you to get creative! Even though these beers are very nice and refreshing on their own, the addition of syrups made from tasty and interesting fruits can add a fun and complex twist of flavors to your Berliners.

Here are two recipes for the classic syrups. It is easy to substitute other fruits or herbs into these recipes to create your own unique versions:

Raspberry Syrup

Ingredients:

- 2 cups of fresh or frozen raspberries

- 1 & ½ cups of granulated sugar

- 1 tablespoon of lemon juice

- ½ cup light corn syrup

- 1 cup water

Preparation:

- Puree raspberries in blender and strain to remove seeds

- Add water, raspberry puree, water, sugar, lime juice and corn syrup in a small saucepan and bring to a boil for one minute. Stir to cool and skim foam off top and refrigerate for one hour before use.

Woodruff Syrup

Known in Germany as Waldmeistersirup, this is a popular type of syrup made from woodruff that is used to sweeten pale ales, as well as the traditional Berliner Weisse. It’s typically green in color.

Ingredients:

- 1 bunch sweet woodruff

- 800 g sugar

- 500 ml water

- 125 ml lemon juice

- 1 teaspoon citric acid

Preparation:

- Combine the water, sugar, lemon juice and citric acid in a pan and heat gently until the sugar dissolves to form a syrup.

- Take off the heat and set aside to cool.

- Meanwhile, strip the leaves from the sweet woodruff and stuff into a 1 to 1.5 liter

- When the syrup has cooled, pour into the bottle with the sweet woodruff leaves.

- Transfer to the refrigerator and allow to steep for about 5 days, turning every day, or until the woodruff flavor has been imparted into the syrup.

- After five days strain the syrup (discard the leaves) then pour the liquid into a clean bottle and store in the refrigerator.

In Germany it’s common to add a little green food coloring to the woodruff syrup to make it green. The syrup is used as a cordial, to be mixed with water. In addition to serving as a beer flavoring, it can also be poured over pancakes or ice cream.

Ending Thoughts

With summer rapidly approaching, the fact that Berliner Weisse is a super crushable style makes it the perfect beer to get you started on your journey into sour and funky brewing. The style is simple to brew. From its simple grain bill to its quick souring method, Berliner Weisse is sure to become a new favorite! Add in the fact you can make all sorts of fruit syrups or even just add fruit right into secondary and the limits are endless! So fire up those mash tuns and kettles and get brewing!

As always please email us with your questions and comments.

Cheers and Keep it Funky!

Cale “Sour Brew” Baker

Dr. Lambic on Berliner Weisse

There is no doubt that a well-brewed Berliner Weisse offers its fans a tasty, clean, and easy drinking sour beer. Though, for me, the concept of what this style of beer represents is even more exciting than the resulting beer itself… And this concept is ACCESSIBILITY. The fact that this odd little sour beer, which had become nearly extinct in its home region, has become popular among American craft beer drinkers has done a great deal to promote the entire spectrum of sour beers into the mainstream. Berliner Weisse has done this by asking brewers a simple question: Can you make a sour beer as quickly and easily as the other ales in your portfolio? We now know that the answer to this question is a resounding YES! However, this was not always the case. When I started brewing about 7 years ago, the conventional wisdom was that Berliner Weisses took about 3 months to properly mature. The concept of single strain Lactobacillus fermentation, which I have been proud to help popularize, allows us to create these beers in a matter of weeks. This is exciting because it makes the idea of keeping a sour beer on draft as a full-time offering a very plausible option for both home and craft brewers.

But conceptually, that’s not all that Berliner Weisse has to offer. Berliner Weisse also stacks the deck by being session strength, devoid of flavors and aromas that we would call “funky”, and by generally avoiding levels of acidity that could melt your face off. The fact that these traits work so well in this beer opens up the creative brewer to start incorporating them in a variety of Berliner Weisse inspired sour beers. Do these beers need to be 50% wheat and 50% pilsner malt? Certainly not.. Why not 100% Pilsner? Why not add some Vienna? How about Maris Otter? Could I use Oats and Rye? The answer to all of these questions will be: Of Course!

What about hop bitterness and flavor? Can I use more? What about a dry-hopped sour pale ale? A session-able sour English Mild? I’ve never had one… but that doesn’t mean it couldn’t be delicious!

Can I add fruits, vegetables, spices? Knock yourself out! You’ll know in a couple of weeks whether your plan actually works, rather than waiting 6 months for sour beers with a more complex fermentation scheme.

You want more complexity you say? Fine.. Split your batch. You can drink the finished half of your Berliner-esque beer for the next two months while the Brettanomyces and home-grown peaches you toss into the second half transform your beer into something unique, and possibly extraordinary!

But Dr. Lambic… I tried a few Berliner Weisses at a local festival that both smelled and tasted like toe-jam, vomit, or literally poop. I don’t think I like this style? Well my friend, in this case you’ve never actually had the style. Because a properly brewed Berliner Weisse (or any beer made using a fast-souring process) should never smell or taste like one of the most vile substances to come out of the human body. When properly made, these are delicious beers that you can drink in large quantity (always drink responsibly!).

The bottom line with Berliner Weisse is that if you haven’t yet tried your hand at brewing one, you absolutely should! And once you’ve rocked out a great version of the classic style, let your imagination run wild with possibilities! Trust me, you, your friends, and/or your customers will not be disappointed with steady access to this outstandingly drinkable sour beer and all of its creatively concocted cousins!

Cheers!

Matt “Dr. Lambic” Miller

If you enjoyed this article, we also recommend reading:

Understanding, Brewing, and Blending a Lambic Style Kriek

References:

“BJCP Style Guidelines.” BJCP Style Guidelines. Beer Judge Certification Program, n.d. Web. 24 May 2016.

Kuplent, Florian. “Berliner Weisse-From Past to Present.” Morebeer.com. Morebeer, 07 Feb. 2013. Web. 20 May 2016.

“Syrup Recipes, Cocktail Sweeteners and More Additives.” Syrup Recipes, Cocktail Sweeteners and More Additives. Cocktails of the World, n.d. Web. 26 May 2016.